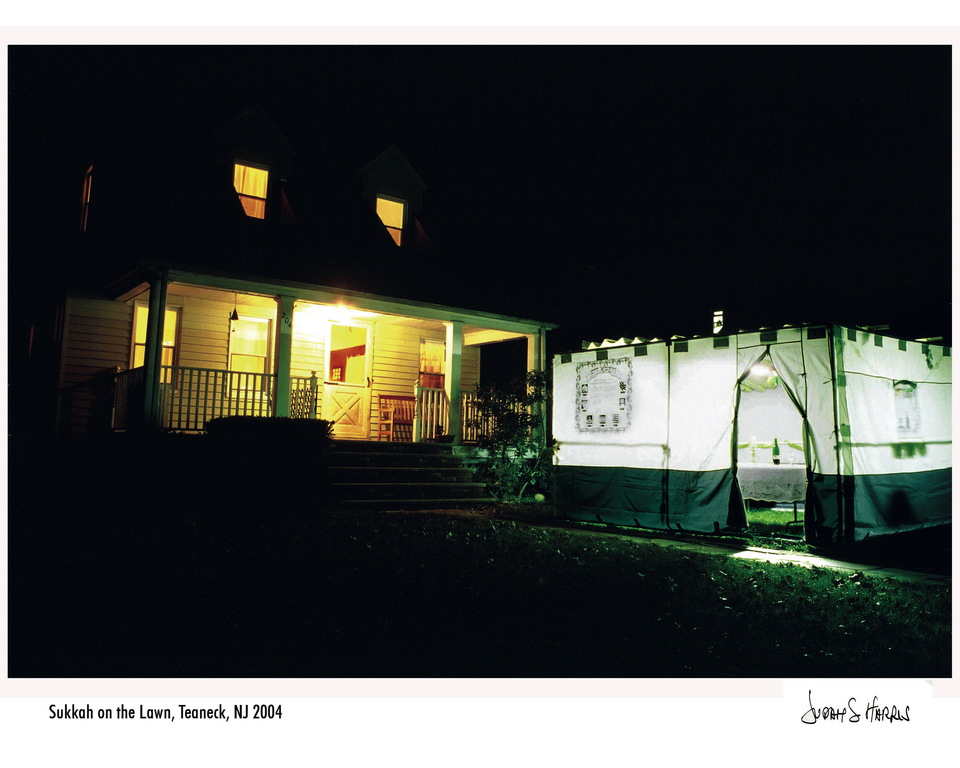

The permanent sukkah: A Sukkos essay inspired by a color photograph

By Judah S. Harris

“All seven days, one makes his sukkah permanent and his house temporary” (Mishnah Sukkah 28b). The opening line of the last Mishna in the second chapter of the tractate of Sukkah instructs us to adjust our definition of dwelling. For seven days, and one additional day outside of the Land of Israel, our homes — which come in all shapes and sizes — are to be viewed as the more temporal, and the simpler structures that we have erected, the more permanent, the more established (kavuah). In the explanation given by Rashi and other commentaries, we see that this permanence of the sukkah is not a comment on its physical construction and durability, no matter how many nails or screws or how much rope we use, but rather on the activities that we engage in inside the sukkah. All the basic essentials of our home life should take place there and the Talmud goes on to list that a person should bring his fine utensils and linens into the sukkah; one should eat and drink there, relax there, learn there. A couple of pages earlier the Talmud also mentions the requirement to sleep in the sukkah. This is all derived from the section in Emor dealing with the laws of the festivals, where the Torah commands us to dwell in the sukkah for seven days: “Ba’sukkos taishvu shivas yomim.” The rabbis learn out “Taishvu, k’ain taduru,” that our existence in the sukkah should approximate, even mirror the way we live at home the rest of the year. There should be a permanency, in attitude and action, to what is admittedly a temporary structure. Notions such as the fluctuation or fluidity of permanence and the temporal should be familiar to all of us. Sukkos follows ever so closely the yomim noraim, a period where we find ourselves in a precarious, uncertain place. We now celebrate our forgiveness and a new beginning, but with the understanding that there really is no permanence in an ultimate sense, only protection afforded us by G-d. In Emor the Torah states that the sukkah is a reminder for the generations of how G-d protected the Jewish people when they left Egypt, as they made their way from the house of slavery to a more permanent homeland of their own (ki vasukkos hoshavti es Bnei Yisrael). And what were these sukkos with which G-d protected his people? One opinion is that these were actual sukkos, physical structures. Another, and the more stressed opinion, is that the “sukkos” mentioned refers to the seven Clouds of Glory (one above and below, four on each side, and one to lead the way) that protected the people in the desert. According to some, both are true: G-d provided the Jewish people with actual sukkos and then surrounded them with the protective clouds. The physicality of our own constructed sukkahs clearly acknowledges the understanding that G-d provided actual structures for His people. But the idea that “ki vasukkos hoshavti” refers to the Clouds of Glory is also present when we remember that the permanence and temporal of the physical world are easily interchangeable, and only the Divine protection is constant. The idea becomes clearer in the sukkah as we sit in the shade of the schach, with a semblance of roof above our heads but still able to see the heavens above. We are “b’tzilah d’mehaimanusa, sitting in the shade of our faith in G-d,” the term used to refer to these heavenly clouds that accompanied the Jewish people in their journey. In our own journeys we seek that constant of faith in G-d to ever protect us in a world where that which we call temporal and that which we consider permanent sit right alongside each other, often encroaching on each other. On Sukkos, that proximity is hard to miss. The temporary, now permanent sukkah we have just erected on the balcony, in the backyard, or even on the front lawn is very much within eyesight, and often mere feet away from the permanent, now temporary home we live in year round. Judah S. Harris is a photographer, filmmaker, speaker and writer. His work can be seen by visiting www.judahsharris. com/visit.The permanent sukkah: the back story

The photo on the front page was taken during a casual yom tov stroll in Teaneck in 2004. A couple of years later I saw the possibility of an essay.

I saw this nice canvas sukkah sitting on a front lawn alongside a Victorian home (maybe it’s really a Colonial with a nice porch). I was on a street just a block from where I grew up. Though headed to lunch, I backtracked a few feet to ponder what intrigued me about the scene. Seemed like a photo to me. And I thought dusk would be a good time to catch the light remaining in the sky along with the light coming from the inside of the sukkah.

So after the holiday I went to take a photograph, which is titled Sukkah on Lawn. Yes, I propped the table with a bottle of wine to draw the eye visually into the sukkah. And I made sure that the porch lights were on too. To be honest, I missed dusk, busy as I was deciding where exactly to plant the three legs of the tripod (I think I found the right place).

I wrote the essay because the picture got me thinking. Usually we don’t see a sukkah on a front lawn — at least not that often next to a house of this sort. The juxtaposition was not the visual norm. Alongside each other, there was a statement being made about that which is permanent and that which is temporary...

— Judah S. Harris