The stories of Sholem Aleichem on screen

He was the eternal optimist, leaving the shtetl of Kasrilevke for America, taking a risk on the stock market, and she was the ever-critical housewife who stayed behind in the alte heim. “Everyone says that in America, G-d willing, I’ll be a big hit,” to which his wife replies that he is a “certified lunatic.” The optimist is Menachem Mendel, writing to his wife Shayna Sheindel, but it may as well be the author Sholem Aleichem, who also invested in stocks.

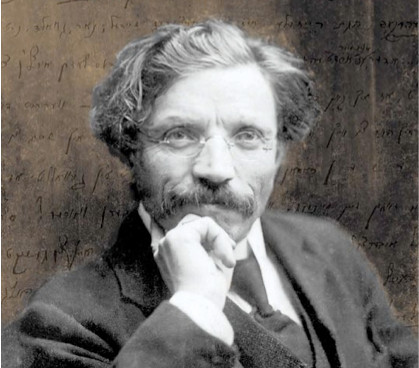

The scene is reenacted in the documentary with separate century-old photographs of an Ashkenazi man and woman hovering into view as they bicker back and forth through their letters. Translated in the Joseph Dorman’s “Sholem Aleichem: Laughing in the Darkness,” the anecdotes exemplify the life of the greatest Yiddish storyteller, born in 1859 as Sholem Rabinowitz, as he rose from poverty to prose, including his failed attempt at stardom in America, and his posthumous fame, which gave Tevye the Milkman immortality on Broadway and the big screen.

A father of four daughters and two sons, Sholem Aleichem often referred to them as his “little republic,” based on each child’s individual concepts of Jewish identity. Inspired by his personal anecdotes, the writer transformed them into Tevye’s seven daughters, who each go on separate paths in their lives.

While Tevye’s departure from his village ends in uncertainty, Rabinowitz’s 1906 arrival in New York was greeted by thousands at the dock, but his first play on Second Avenue, Oysvorf, was such a fl op that he returned to Europe. “He was a failed immigrant,” Dorman said. “My parents had his books on their bookshelf.”

Living on the Upper West Side, Dorman is no stranger to opposing views within the Jewish community and his previous films include the 1997 documentary “Arguing the World,” on the careers of New York’s political Jewish intellectuals, who grew up during the rise of fascism and communism. “They were man said.

Dorman was prompted to take on Sholem Aleichem by his friend Jeffrey Shandler, a professor of Yiddish literature at Rutgers University who organized a YIVO exhibit on Rabinowitz’s failed career in New York. “It seems outrageous at first look that he failed in America, but most immigrants here were young and it was much easier for them to make the transition,” Dorman said.

Borrowing from the large photograph collection at YIVO, Dorman recreated stills of Russian shtetls, wartime devastation, the Lower East Side, and the author at various stages of his life. “They built up this amazing archive from photographers sent to Europe by The Forward in the 1930s. The videos were cap- tured by wealthy American Jews who made home videos visiting their home shtetls.”

To get perspectives on Rabinowitz, Dorman interviewed Yiddish experts that include Dan Miron of Columbia University, author Hillel Halkin, and Aaron Lansky, who founded the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass. The film also includes Hunter College professor Bel Kaufman, who turned 100 in May. A granddaughter of the author, she is the last living person to remember Sholem Aleichem, who died when she was five. Rabinowitz was a traditionalist, but not Orthodox. He was supportive of Zionism, but in a nonpartisan manner. For this reason, he was snubbed by Abraham Kahan, the founding editor of The Forward. But once he died in 1916, every faction claimed Shalom as their own. The socialists admired his working-class characters. Zionists looked at his writings as a throwback to the diaspora. Traditionalists appreciated Tevye’s stubborn Orthodoxy in the face of massive social upheaval. Having told the stories of socialists and a Yiddish author in fi lm, Dorman’s next project, in partnership with Oren Rudavsky, tackles the history of Zionism. “It’s like a trilogy of films with another solution on preserving Jewish identity.”