‘The Forgotten Man’: Viewing the Great Depression

A version of this column was published in 2008.

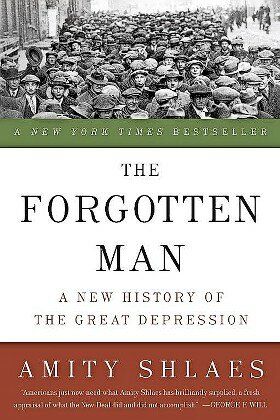

With the economic situation deteriorating each day, anything dealing with the history of past economic disasters is bound to peak our interest. “The Forgotten Man,” published by Harper-Collins, provides us with appropriate reading fare.

In this book, written some time before the 2008 financial crisis, Amity Shlaes’ unusual take on the historic significance of the Great Depression of the 1930s has generated the notoriety that would be the envy of any author. She does not accept the political and economic mantra that FDR was the great American messiah who came along to save the United States from economic purgatory.

In her book, Shlaes, chair of the Coolidge Presidential Foundation, paints a mixed review as to the true effectiveness of the New Deal in solving the woes of the great economic dive that was emblematic of that era. In a first class myth-buster, Shlaes demonstrates time and again where political rhetoric fell far short of political and –– even more telling –– economic reality.

While giving the president his political due, the author points to the misleading idealism of his aides and advisors who spent the money from the US treasury as if it were a personal kitty, actions that sound familiar to today’s news coming out of Washington. Given this atmosphere, a challenge was bound to arise, from an unexpected source that would, in the end, bring down the whole New Deal edifice.

They were known as the Schechter Brothers from Brooklyn. They were kosher butchers who tried to work honestly at their craft within the parameters of the laws of their faith. And, they were loyal New Deal Democrats who hung up a picture of FDR as if it were a religious icon. However, there was a problem –– a big problem: the government bureaucracy and its onerous regulations were driving their meat business into the ground and distracting the owners from their tasks.

In a daring move, these hardworking religious kosher butchers challenged the various regulations of the National Recovery Act, perhaps the most socialist piece of federal law ever enacted by our government, and proceeded to take legal action challenging same. No major corporation had done so until then, something that was to bring much pride to our community at that time.

In chapter eight, “The Chicken Versus the Eagle,” Shlaes artfully details the personalities of all those concerned as well as the actions and motivations of all the main players. The irony of the situation is never lost on both the narrator’s part, as well as on the reader. The author makes sure of that. This was and still is the classic David versus Goliath conflict; David wins and the narrator cheers.

Their plaint goes all the way to the US Supreme Court, thus involving legal personalities about whom legends are written about to this day. In a landmark decision, these kosher butchers, in the name of integrity and fairness, win their case and thereby disassemble the cornerstone of their much beloved New Deal. One unintended result was that Brooklyn Jews continued to get their ample supply of kosher meat products.

In an interesting comment at the end the author notes the following:

“The Schechters went back into business after their Supreme Court victory, according to their descendent Glen Asner. In a note to the author, Asner wrote: ‘Their major political concern in the 1930s was antisemitism. They believed that if Roosevelt had not solved the problems of the Depression, the US could have gone the way of Nazi Germany. Their overarching political concern was the condition of the Jews. That said, the main topics of discussion around the house were horses, stocks, and business,’ Asner thinks it likely that the Schechters voted for Roosevelt all four times.”