Tashlich more than Marie Kondo waterfront purge

Earlier this month, Royal Auction House in Toms River, NJ, sold an 1806 illustrated, handwritten Tashlich guide for $5,000. Last month, Appel Auction in New York offered but didn’t sell a 19th-century painting depicting the rite. Years prior, Kestenbaum & Company in New York sold an early 20th-century Austrian painting on glass of four men saying Tashlich for $8,000.

The Israel Museum owns a 1905 Tashlich lithograph by Polish artist Karl Felsenhardt, and the collection of New York’s Jewish Museum includes a 1984 abstract painting titled “Tashlich,” a 1955 Robert Frank photo “Yom Kippur-East River, New York City” and a 1989 image of an Ethiopian congregation performing Tashlich.

These and other artful depictions of the High Holiday ritual at first appear contradictory. The rite symbolically casts out an individual’s sins — typically into a body of water with fish — and the idea of preserving the Jewish holiday version of a Marie Kondo purge seems to miss the point.

But the Tashlich ritual is about something deeper than purging, experts say.

“Tashlich is not about forgetting things or obliterating what we have done,” Shalom Carmy, assistant professor of Jewish philosophy and Bible and editor of the journal Tradition, told JNS. “It is not a performance of willed amnesia. It is an expression of our plea for Divine mercy and forgiveness.”

Dismissing sins is different from forgetting those offenses, Carmy told JNS.

Jon Levenson, a professor of Jewish studies at Harvard University who researches the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible, told JNS that Tashlich is about neither decluttering, simplifying one’s life nor attaining joy.

“It is, rather, a symbolic enactment of repentance, a painful process that requires an unblinking confrontation with our own mortality and with our violations of the will of G-d,” Levenson said. “Such a confrontation is not fun, but it is an essential part of the traditional Jewish spiritual vision — whether Tashlich, a ceremony of apparently medieval European origin, is practiced or not.”

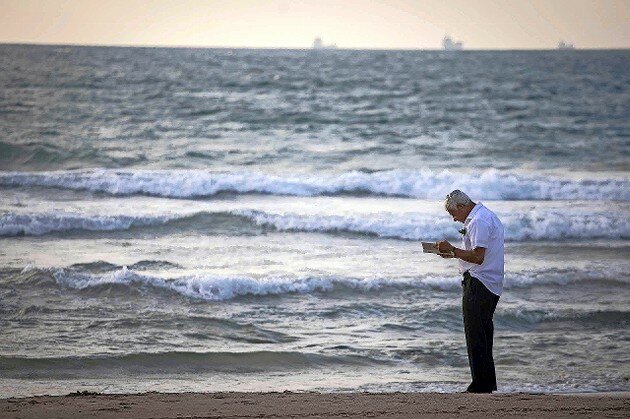

As part of this specific rite, worshippers stand before a body of water with fish, although in a pinch, one can recite the prayer before a dried-up river or even a bucket of water, per the Chabad website. The Hebrew name refers to “casting out” sins — perhaps in connection with Micah 7:19, which states, “And cast out (tashlich) all of their sins into the sea depths” — and adherents cast pieces of bread, stones or other items into the water and shake out their pockets.

Many perform the ritual communally on the first day of Rosh Hashana or the second day if the first is Shabbat. Rabbinic tradition prohibits feeding birds or fish on the holiday, for those doing Tashlich on Rosh Hashana.

The interfaith site 18Doors refers to the rite as “a fun outdoor tradition,” but many, who see social gatherings as antithetical to the spirit of the solemn rite or who have practical limitations, do Tashlich as late as Hoshana Rabbah.

Still others do not do Tashlich at all, perhaps because the custom risks trivializing the work of attaining forgiveness.

Sholom Mimran, the rabbi of the Orthodox Congregation Dor Tikvah in Charleston, SC, told JNS that Tashlich is a confusing ritual “because as Jews, we don’t believe in quick fixes.”

“So what’s the point even?” Mimran said.

Over Rosh Hashana, he heard an explanation that he found appealing: Tashlich makes sins seem external and easy to discard.

“The message being that our shortcomings aren’t our identity. This puts repentance into an easier perspective,” he said. “The irony of people misunderstanding Tashlich has meant people feeding fish.”

51.0°,

Light Rain

51.0°,

Light Rain