Shafran: The art of growth

Issue of May 8, 2009 / 14 Iyar 5769

I don’t often ride the New York subways, but not long ago I found myself leaving a train deep beneath Brooklyn, at the borough’s cavernous Atlantic Street station. And I was surprised to be greeted, amid all the usual squalor and bustle, by a large and exquisite reproduction of “The Starry Night,” Vincent Van Gogh’s eerie painting. I’m no art aficionado but the famous rendering of a haloed moon and stars in a swirling blue firmament has always moved me. What in the world — or underworld — though, was a copy of the painting doing on a subway station wall?

Then, turning to find the track I needed, I found myself face to face with an unmistakable Monet pond scene. Nearby, I noticed with increasing amusement, were cubist visions by Picasso, Warholian soup cans and various other copies of paintings, drawings and photographs whose originals hang in museums.

Or, as I discovered, a museum — New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The posters were part of an advertising campaign to lure subway riders to visit the originals.

Clever, I thought, and a nice touch for a famously unrefined environment. Then my thoughts drifted.

The reproductions before me were, at least to untrained eyes like mine, virtually indistinguishable from the originals. I’m sure the textures of the brushstrokes are evident in the actual paintings, and they alone, after all, were produced by the artists’ hands. But great pains had been taken to present subway patrons with top-notch copies of the MOMA possessions. The results, had they been hanging on a museum wall, could probably have fooled most people.

Yet the originals are, well, authentic, and priceless; and the copies mere copies, worth only their printing costs (and copyright fees).

People, too, I ruminated, can be real or ersatz. Some are just what they seem. Others, though, are, in effect, cheap copies, pretending to be what they project but lacking authenticity of character, the brushstrokes of the soul.

There are, for instance, genuine leaders dedicated to advancing the interests of those they lead, and shameful imitations, demagogues donning mantles of power for their own personal gain. There are true scientists, open to wonder and dedicated to discerning natural truths; and there are counterfeit ones, duly credentialed but without the sense of objectivity that underlies the genuine pursuit of truth. There are deeply religious people who understand that there is a greater Power than any temporal one, Whose will human beings must strive to discern and follow. And there are charlatans, pretenders to spirituality, sometimes obvious, other times not. It is no different in the observant Jewish community, where there are sincere men and women pledged to the laws and ideals of the Jewish religious tradition, but also people who dress the part but whose clothes are just costumes.

But those are the extremes; human nature isn’t a dichotomy. There are also leaders who want to do what is right but succumb at times to doing what’s best for themselves; scientists who are basically objective but occasionally allow their biases reign; religious people whose deepest desire is to serve G-d but who are vulnerable to laziness, jealousy and anger.

That describes many of us, I think. But we aren’t fakers for the fact. There is a great difference between pathology and imperfection, between being hypocritical and being human.

The Talmud relates how, for a period of time, under the leadership of the illustrious sage Rabban Gamliel of Yavneh, the study hall was open exclusively to students whose “insides were like their outsides” — who were precisely what they purported to be, righteous scholars.

Rabban Gamliel’s successor, however, loosened the requirement –– for the better, the Talmud implies.

So it would seem that even those of us who are less than perfectly coherent need not despair. My revered mentor, Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg, of blessed memory, noted that the Talmud’s wording is instructive. We are not exhorted to bring our “outsides” into line with our “insides” –– to achieve spiritual purity and then adopt its signifiers –– but rather the other way around. We are permitted, even required, to outwardly emulate

those more spiritually accomplished than we, to embrace acts of observance and goodness, even if our souls are not yet as pure as our clothing. “A person is acted upon,” in the Sefer Hachinuch’s words, “by his actions.”

And yet, the “insides like outsides” ideal clearly remains the ultimate goal, not only for scholars but for us all. We may not yet have achieved –– and, as the imperfect creatures we are, may never achieve –– full coherence, but we must strive for it all the same. The only excuse for not being there is that we’re trying to get there. And as long as we are honestly working toward our goal, our efforts bring us closer.

How fortunate are we humans. A copy of a Van Gogh cannot ever, no matter how hard it tries, grow into the real deal.

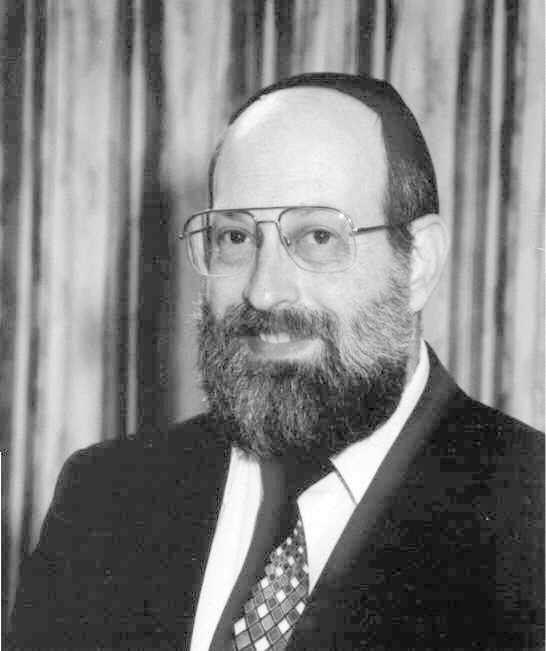

Rabbi Shafran is director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America.