Israel faces risks as Sudan slips into chaos

The warlords who have brought untold misery to Sudan since it achieved its independence from the United Kingdom in 1956 are hardly loosening their grip. Over the last week, Africa’s third-largest country has been plunged into a bitter civil conflict between two rival rulers, resulting in hundreds of dead, thousands of wounded and tens of thousands of refugees spilling over its borders into neighboring states.

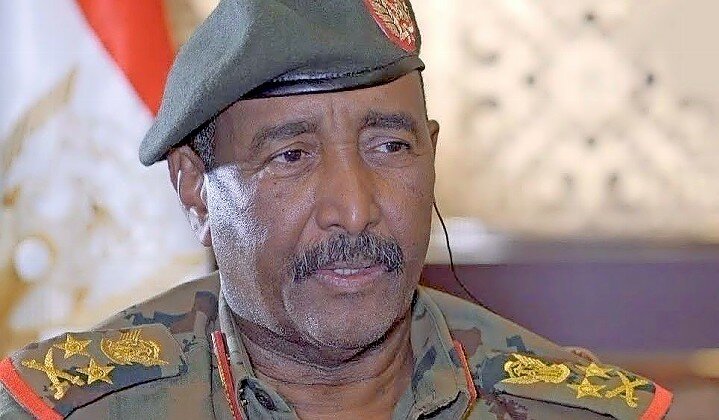

The proximate roots of the present crisis lie in the 2019 coup that led to the overthrow of the Islamist dictator of 30 years, Omar al-Bashir, following months of popular protests against his regime. An uneasy transitional council then took power, thwarting one military coup in September 2021 before another the next month led to the dismissal of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and replacement by the head of the Sudanese military, Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Under al-Burhan, Sudan remained nominally committed to a democratic transition, through a December 2022 agreement that specified April 1 of this year as the deadline for a final resolution. The agreement included a commitment to integrate the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), commanded by Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, into the national armed forces. But that didn’t happen after Dagalo (better known by his nom de guerre, “Hemedti”) declared that he wanted to postpone the process for 10 years. However, al-Burhan would not agree to a postponement longer than two years, setting the stage for the current brutal fighting.

The dispute between al-Burhan and Hemedti is not ideological or religious. As is true with many of Africa’s wars, the current strife in Sudan is about control of resources, with Hemedti’s RSF jealously guarding its control over the lucrative gold mines in the province of Darfur.

Consequently, there is no natural partner for Western democracies in either leader; nor is there any decent political project worthy of international support. On top of that, it’s hard to see how a global consensus on Sudan could crystallize, at least beyond the obvious realization that a renewed collapse into civil war is in no one’s interest.

The world is more perilously divided now than at any other time since the end of the Cold War, and both Russia and China have long pursued economic and strategic goals in Sudan, meaning that they are unlikely to play ball with the United States or other Western nations, particularly as long as the war in Ukraine and the tensions over Taiwan persist.

One factor that makes this particular conflict in Sudan unusual is that Israel — once regarded as an implacable foe in Khartoum — is now a player, having signed a normalization agreement with the post-Bashir government in 2020, as part of the much-vaunted Abraham Accords reached with a handful of Arab states under the auspices of the United States.

According to a report in Axios, the process negotiated over the last three years between Israel and Sudan has afforded the Israelis unique insight into the mindsets of both al-Burhan and Hemedti, and what may influence them. Israel reportedly wants the fighting to stop immediately, fearing that war will derail the formation of a civilian government and therefore the peace agreement.

For the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, facing unprecedented unrest at home and renewed criticism of its treatment of the Palestinians abroad, every Arab state that signs up for a peace deal with Jerusalem must feel like a vindication. As a veteran member of the Arab League whose fate is closely aligned with its Egyptian neighbor to the north, Sudan’s signature is, as Hemedti might put it, worth its weight in gold.

The problem is that the other states united by the Abraham Accords — namely, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco — are divided when it comes to internal stability. None of these states are democracies, and all of them possess woeful records on human rights, though some are more stable than others.

Sudan is radically unstable, having experienced more coups since independence than any other country in Africa. And as well as being a failed state, Sudan has for much of its existence been a rogue state, providing a base for the late Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden back in 1993. Moreover, in the case of Israel, not every political force in Sudan supports the agreement; when Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen visited Khartoum in February, the People’s Conference Party and the Islamic Bloc, which comprises 10 different Islamic parties, issued statements warning al-Burhan that he had no mandate to make peace with Israel.

For numerous reasons, then, it would be foolish to present the peace between Israel and Sudan — more accurately, between Israel and Sudan’s quarreling military leaders — as permanent.

Yet when Israeli leaders wax lyrically about the benefits of peace with Sudan, it seems as if they are in denial of reality.

While in Khartoum, Cohen paid tribute to a “historic peace agreement with a strategic Arab and Muslim country,” asserting that the “peace agreement between Israel and Sudan will promote regional stability and contribute to the national security of the State of Israel.”

Such sentiments are misplaced in a country where power still comes from the barrel of a gun rather than the ballot box. The issue in Sudan is not which of al-Burhan or Hemedti should rule, but whether either of them can even be considered a legitimate leader.

• Among al-Burhan’s abuses is the June 2019 massacre of peaceful protesters in Khartoum, with hundreds murdered, tortured and raped, and reports of corpses thrown into the Nile River.

• For his part, Hemedti emerged from one of the most monstrous paramilitaries seen during this century — the Arab Janjaweed who engaged in a genocidal reign of terror in the Darfur region from 2003 until 2020.

High-minded notions like the national interest or national reconciliation are utterly foreign to both men, for whom political power is primarily an opportunity to consolidate their personal wealth and eliminate their rivals.

Israel can try and broker a truce between the thugs, but even if one is achieved, it won’t last. Peace is only possible in Sudan if the causes of nearly 70 years of instability are meaningfully addressed.

When it comes to nation-building, Israel has a wealth of experience. But al-Burhan and Hemedti will listen to outsiders only for as long as it suits them.