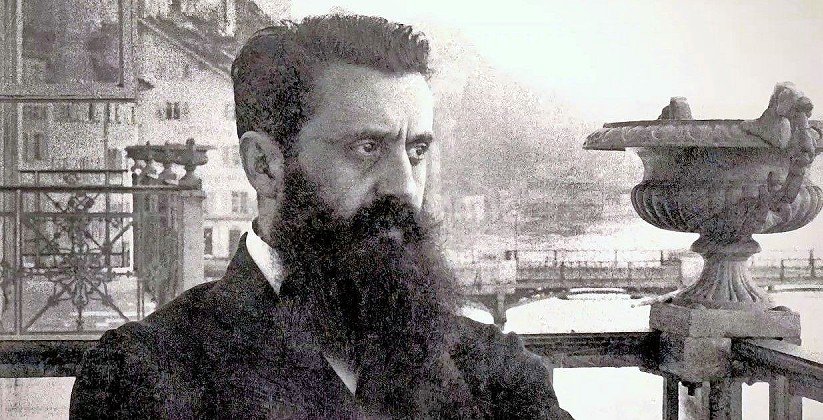

Herzl was gone but his vital message survived

Excerpted from the new three-volume set “Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings” edited by Gil Troy, the inaugural publication of The Library of the Jewish People.

In 1897, in the short story, “The Menorah,” Theodor Herzl essentially described himself when he wrote about a man who once “deep in his soul felt the need to be a Jew,” and who, reeling from Jew-hatred, watched “his soul become one bleeding wound.” Finally, this man “began to love Judaism with great fervor.”

Herzl saluted his step-by-step Judaization and Zionization. Celebrating Chanukah, he delighted in the “growing brilliance” candle by candle, gradually generating more and more light.

The “occasion became a parable for the enkindling of a whole nation.” Flipping from the reluctant, traumatized Jew he had been to the proud, engaged Jew he was surprised to see in the mirror, Herzl admitted: “When he had resolved to return to the ancient fold and openly acknowledge his return, he had only intended to do what he considered honorable and sensible. But he had never dreamed that on his way back home he would also find gratification for his longing for beauty. Yet what befell him was nothing less.”

Herzl concluded: “The darkness must retreat.”

Seven years later, Herzl spelled out Zionism’s dynamic power, its spillover effects. “For inherent in Zionism, as I understand it, is not only the striving for a legally secured homeland for our unfortunate people, but also the striving for moral and intellectual perfection,” he wrote.

This vision made Herzl a model liberal nationalist. He believed that “an individual can help himself neither politically nor economically as effectively as a community can help itself.”

Articulating the faith in farming and physical labor that would animate Labor Zionism, Herzl endorsed “a Jewish physical therapy which we can make available to our masses, particularly to those from areas where they have an abnormal lifestyle. There is no doubt that people who are made to do farm work and physical labor generally become healthier. This health, in turn, has moral consequences.”

Despite his fin-de-siècle European airs and sensibilities, Herzl’s liberal-democratic Jewish nationalism was a far cry from European colonialism. Herzl’s Zionism would turn Palestine’s Jewish settlers “into permanent dwellers on the land, into real freeholders. They shall live on the land and from the land, not like helpless peddlers with an anxious eye on the market prices.”

This non-exploitative, non-extractive approach would lay a foundation “for the enduring tranquility so ardently desired by the long-buffeted Jewish people.”

Herzl explained at another point that “all this beautiful country needs is the industrial skill of our people. The Europeans who usually come here enrich themselves quickly and then rush off again with their spoils. An entrepreneur should certainly make a respectable and honest profit, but after that he ought to remain in the country where he has his wealth.”

His Jewish state would be a model for others, which included helping its neighbors. In Cairo, while appalled by the British inability to understand what the fellahin [peasant] in Egypt were suffering and learning under colonialism, Herzl exclaimed: “I resolve to think of the fellahin too, once I have the power.”

The ongoing breech over whether to focus temporarily on resettlement in Uganda (actually the Kenyan highlands) and not Palestine, rattled Herzl. This time, the movement proved more resilient than the man. A heart specialist, Dr. Gustav Singer, was shocked to see “a pale, tired, sick patient” in December 1903, instead of the delightful bon vivant he thought he knew from the newspapers.

“I was soon forced to realize that death was already lurking in the shadows,” Dr. Singer would recall. “His pulse was irregular, the heart output greatly impaired” and “there were the circles around his once so fiery eyes.”

On April 30, 1904, after further deterioration, doctors prescribed a six-week retreat at Franzensbad, a mineral springs resort. A week later, Herzl wrote his chief lieutenant David Wolffsohn: “Don’t do anything foolish while I am dead.”

On July 2, Herzl finally updated his mother about his health crisis. His comrade Rev. William Hechler was the last non-family member to visit him. Hechler, who had written a book in 1884 titled “The Restoration of the Jews to Palestine,” had bonded with Herzl immediately upon the publication of “Der Judenstaat.”

Herzl summed up his differences with his friend by saying, “Hechler declares my movement to be a ‘Biblical’ one, even though I proceed rationally in all points.” The good reverend would record the great Zionist’s last words: “Greet Palestine for me. I gave my heart’s blood for my people.”

At five o’clock in the afternoon of July 3, 1904, Theodor Herzl died. Thousands mobbed his funeral four days later. He was buried in Vienna next to his father, “to remain there,” Herzl’s will directed, “until the Jewish people will carry my remains to Palestine.”

Long before Israel reinterred Herzl’s remains on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, the Jewish people carried his message of peoplehood and statehood, of giving up on Europe because of its antisemitism, but not giving up on liberal ideals, European sensibilities or the world.

Demonstrating this global vision, one Herzlian character in his novel “Altneuland” announced that following “the return of the Jews, I would also like to help prepare the return of the Negroes.”

The character, expressing Herzl’s commitment to social justice, then explained how national pride engenders world peace: “Every human being should have a home. Then they will be kinder to each other. Then people will love and understand each other better.”

Searing eulogies from Herzl’s followers were expected. The loyal Wolffsohn proclaimed at his funeral that Herzl’s name will “remain sacred and unforgotten for as long as a single Jew lives on this Earth.”

In Plonsk, Poland, a 17-year-old Zionist felt shattered. Back when he was ten, David Green had heard that “the Messiah had appeared in one of the foreign cities … a wonderful man, taller than others, good looking, his radiant face adorned by a black beard.”

Now, this teenage Zionist worried about this “great loss to our unfortunate suffering People. There will not arise again in our midst such a wonderful man who combined the bravery of the Maccabees, the purposefulness of David, the strong devotion of Rabbi Akiva who died while reciting ‘God is One,’ the humbleness of Hillel, the beauty of Rabbi Yehudah Hanasi, the fiery love of Rabbi Yehudah HaLevy.”

“And yet,” the man who five years later would change his name to David Ben-Gurion concluded, “Here am I today, more than ever certain of our victory, and certain that there will come a day when we will return to our Land, the Land of poetry and truth, the Land of prophecy of the prophets.”