Behind my continuing fascination with Hebron

My fascination with Hebron began decades ago when I was selected by the American Jewish Committee to join a group of “disaffected Jewish academics” who had never been to Israel for a sponsored visit to the Jewish state.

I had not paid attention to Israel until June 1967, when I turned on the television while caring for my sleeping baby daughter. It was the moment when triumphant Israeli soldiers reached the sacred Western Wall in Jerusalem’s Old City. I was momentarily fascinated, but fathering and teaching were my priorities. Still, a free trip to Israel was enticing, and I knew that I was qualified. So did AJC.

When our bus entered Hebron for a meeting with the Arab mayor, we passed a massive stone building with two high towers. “What’s that?” I asked our guide, Tuvia. “Machpelah,” he responded. “What’s that?” I repeated. He replied: “The burial site of the biblical patriarchs and matriarchs,” about whom (despite four tedious years of Hebrew school as a young boy) I knew little.

Inside the auditorium, the mayor summarized Hebron’s history. Jews were not mentioned. While he was taking questions, Tuvia whispered: “Ask him where his family was in 1929.” Why then? I wondered. But I raised my hand, was recognized and asked Tuvia’s question. The mayor immediately turned away to take another question.

That trip to Israel was transformative. I applied for and received a Fulbright professorship at Tel Aviv University. But I chose Jerusalem — the other ancient holy Jewish city that had fascinated me — for our year-long family residence. Since I had only one teaching day a week, I enjoyed ample opportunity for exploration, especially in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City and the haredi neighborhood of Mea Shearim. But I had not forgotten Hebron.

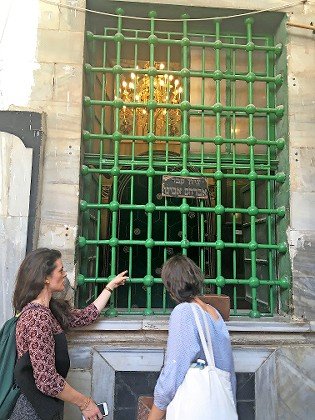

My return, ironically, was at the invitation of Ibrahim Kara’in, an Old City antiquities dealer who I had befriended during visits to his fascinating shop. The Israeli soldier guarding the Machpelah entrance looked carefully at him and scrutinized my passport before clearing us for entry. (Perhaps he was puzzled that a Jew would have an Arab guide to the sacred Jewish shrine.) I was awed by the beauty of Isaac Hall, the centerpiece of Machpelah. I knew that I would return.

• • •

My Tel Aviv colleague and friend Haggai, a Haganah veteran from Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, was puzzled by my interest in Hebron. But he arranged for an Israeli army officer to be my guide. In the Jewish settlement of Kiryat Arba, a short walk up the hill from Machpelah, I had a fascinating conversation with Rabbi Eliezer Waldman, one of the leaders of the restored Hebron Jewish community.

On a subsequent visit, I met with Elyakim Haetzni, a Kiryat Arba lawyer and another founder of the reborn community. Like Rabbi Waldman, he became one of my best Hebron teachers.

With English-language spokesman David Wilder as my guiding mentor, I returned several years later. I had begun to imagine that I might eventually write a history of the Hebron Jewish community, by now home to 700 passionately committed Zionists. He arranged for a visit to the Avraham Avinu quarter, destroyed during the 1929 Arab rioting, and its beautifully restored synagogue. Armed Israeli soldiers were conspicuously posted on a nearby roof. The necessity for their presence was unsettling but reassuring.

My Hebron visits climaxed when I joined the massive flow of Kiryat Arba residents and many hundreds of Israelis to Machpelah for the reading of the Torah text (Genesis 23:2) that recounts Abraham’s purchase of a burial site for Sarah. Irrevocably, it connects Jews to their promised land, embedded in Hebron. To be at the bedrock of Jewish history as the biblical narrative was recited enclosed me within a community of Jewish memory where Jewish history in the Land of Israel began.

Why, I have occasionally been asked, did I become so strongly attached to Hebron Jews who, for many, are pariahs of the Jewish people? My response: As a Jew and historian, I had learned that the sanctity of Hebron (like Jerusalem) must forever remain embedded in Jewish identity and memory.