Stanley Smith: Inspired by a Rabbi

In the 1960s, the Board of Education barred Stanley Smith, a 27 year old industrious electrical contractor, from bidding for electrical work, implying that Smith was “too young and didn’t know what to do.” His mentor told him to go “right to the mayor” even though Smith said that he didn’t know him. When he was stopped by a police officer for lack of an appointment at City Hall, Smith took down the officer’s badge and name saying that he was there to report corruption in the Board of Education, a front-page story in the New York Post that day. The officer then ushered Smith in to see Mayor Robert Wagner who was at a meeting with Abe Beame.

“There was nothing stopping me,” explained Smith. “I go right to the front door. Rabbi Kalmanowitz gave me the chutzpah.”

Stanley Smith, aged 80, president of Morales Electrical Contractors in Valley Stream, divides his time between Manhattan and Lido Beach. He has many interconnected stories to tell, his eyes piercing and direct under a head of thick white hair. Smith is chairman of the Mirrer Yeshiva Archives Committee, and he holds out letters from Simon Weisenthal and Hubert Humphrey, spreading out photos of himself, ubiquitously Zelig-like, but with more of a pivotal role, with actors, politicians and international figures from over 60 years of networking.

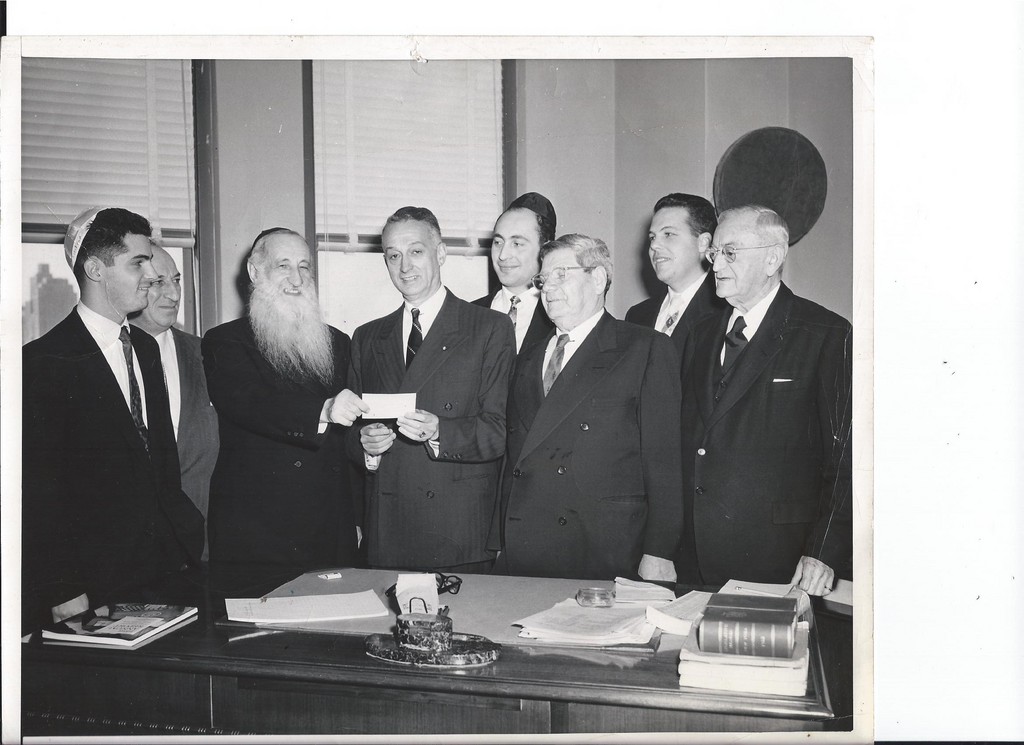

But above all, he credits his success and his outlook on life to a man he calls his mentor, Rabbi Avrohom Kalmanowitz, zt”l, who was instrumental in saving the Mirrer Yeshiva in its entirety from the flames of World War II, and worked to save Jews from Hungary and Egypt as well. “He was like Moses of our generation,” said Smith. “I was privy to a lot of his works.” Holding a black and white photograph of himself as a young man with Rabbi Kalmanowitz, Smith said, “I was touched by an angel, here’s my buddy, I revered this man.”

“He gives more than most people (to the Mirrer Yeshiva), “ said Rabbi Pinchos Hecht, of Far Rockaway, Executive Director of Mirrer Yeshiva, of Smith. “He’s on the Board of Trustees. He cares about the Jewish people; he cares about others. He met Rabbi Kalmanowitz as a young man and was inspired to think and do for others.”

Stanley Smith’s father, born Abraham Isaac Kuznitzoff, meaning blacksmith, came to the U.S. from Belaruss at age 11. He worked with his brother, an electrician, opening his own business, A.I. Smith, in Brooklyn in 1933 when Stanley was born. Stanley accompanied his father to work from age six and met Rabbi Kalmanowitz in 1954 when they did the electrical work for the Mir Yeshiva building in Brooklyn. Stanley was very impressed by the rov. “He was phenomenal,” Smith said. Smith’s father died in 1956 when Stanley was 23; his 30-year-old brother died a week later. Stanley took over the business.

Rabbi Kalmanowitz was a rosh yeshiva and president of the yeshiva in Mir, Poland before WWII, explained Hecht. A student of the Chofetz Chaim and close to Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, Kalmanowitz helped the Mirrer Yeshiva in Europe. After all the yeshivas fled to briefly independent Vilna in Lithuania, Kalmanowitz secured visas from Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat serving in Kovno, and funding for the trip across Russia to Vladivostok and Kobe, Japan. Rabbi Kalmanowitz was able to get a visa to the United States in 1940 and arranged support for the entire yeshiva, and other Jews who fled with the yeshiva, while in Kobe and for the six years after its transfer by Japan to Shanghai.

Following the war, the yeshiva left Shanghai and formed three institutions: the Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn, Yeshivas Mir in Jerusalem and Bais Hatalmud, also in Brooklyn.

Rabbi Kalmanowitz also helped found the War Refugee Board and worked with Rudolf Kastner to help free 1,355 Hungarian Jews from Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp in 1944. “He tried to save the leadership so there would be a future,” stressed Rabbi Hecht. He also saved 20 Jewish men from Egypt.

Smith recounted that at the end of WWII, General Eisenhower telegrammed Rabbi Kalmanowitz that he was “coming close to the camps” anticipating finding survivors and asked “what do I do?’ “Send them Bibles and blankets,” wrote back Kalmanowitz. “Confirmed,” noted Eisenhower, “800 Bibles and 150,000 blankets.” Smith noted that they remained close from then on. He also related that Rabbi Kalmanowitz was sent by the State Department to warn the King of Morocco of an assassination and coup attempt. The king thanked the rabbi.

Kalmanowitz also corresponded with Simon Wiesenthal to attempt to capture and prosecute Adolf Eichmann. In a prophetic letter, Kalmanowitz wrote: “It is not only my desire to prosecute Eichmann, but to stop his diabolical acts against the free world. The acts of aggression on the part of the Arabian people and the inflammatory statement made publicly by King Saudi, make it very evident that they are being influenced by the Nazis, as their tactics and language are similar to those used by Goebbels and Hitler in their campaign to conquer the world.”

Smith also recalled helping procure papers following Rabbi Kalmanowitz’s death in Florida, to bring the body back to New York and send it on to burial in Israel.

He read aloud from an entry written by Hubert H. Humphrey, President Lyndon Johnson’s Vice President, in a memorial journal on Rabbi Kalmanowitz’s passing: “Until the end he was seeking refuge for the oppressed and founding schools to keep the light of wisdom burning. It was a benediction to have known him and because of men like him no oppressor will crush the spirit of men.”

Smith has many stories to tell of behind the scenes maneuvering, his ties and “relationships,” a term he stresses, to influential people and events. He admits to ties with law enforcement, unions, his meeting famous people and maintaining these relationships over time, introducing people from his different circles to each other, further growing spheres of influence. He was invited to join the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce in 1968, arranging events and expanding it with a Welcome Back to Brooklyn and a Brooklyn Goes Global event, inviting international businessmen, celebrities, and politicians. He has “relationships” with diverse people including Chinese politicians and CFOs, businessmen from the Ukraine and Russia, people from Cuba, and the U.S. government. He’s been photographed with Mohammad Ali, Carl Bernstein, Joe Frasier, Henry Kissinger, Jimmy Carter, Ruth Westheimer, Judd Hirsch, Chinese officials and businessmen, Cuban officials and many other influential people. He said his relationship with the Chinese helped him negotiate the release of 23 Americans arrested on charges of spying when their plane went down in China in 2001.

“There is no ending to this,” said Smith. “I tie people together. We don’t need many people, but we need a few people who know how to handle things in the right direction. We can do anything; you have to respect them.

“We’ve got to go ahead; the next generation doesn’t know anything,” he continued. “They gave a $25 check to Mir. We gotta wake them up, to raise their consciousness to the eminent danger, not only of anti-Semitism and genocide in the Arab world and Europe, but the Nazi influence. I contributed every year. But nobody’s continuing (Rabbi Kalmanowitz’s work). We have to reach out to government leaders to stop the chaos in the world for Jews and anti-Semitism. You have to promote and plant the seed. It’s like carrying a torch.“ He attributes his success to his relationship with Rabbi Kalmonowitz and often asks himself “what would he do if he was in this problem. He showed me the way to penetrate bureaucracy, which I became an expert on,” he emphasized.

“I can’t wait to get up in the morning,” he said. “I have nachas every morning when I wake up. G-d gives me the gift of this day. I’m going to make this day last forever.”

53.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

53.0°,

Mostly Cloudy