Robertson: Problematic but essential friend

Rev. Pat Robertson was the kind of person who inspired not only love and rage, but a great deal of intellectual confusion. One need only read the exchange between then Commentary magazine edito Norman Podhoretz and his critics over a 1995 essay that the former wrote about what Jews should think about the televangelist who died this week at the age of 93 to see how complicated the debate about him could be.

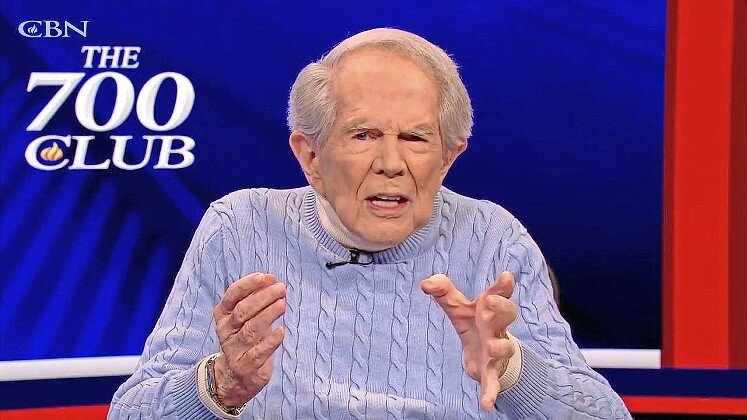

Robertson, the Yale University — educated son of a US senator, founded the vastly influential Christian Broadcasting Network in 1960 and hosted its anchor show “The 700 Club” for 55 years.

CBN brought his brand of Protestantism from the revival tent into the homes of Americans. It heralded the emergence of the evangelical movement from the margins of popular culture to the mainstream and did the same for a brand of Christian conservatism that revolutionized American politics. While his effort to parlay that platform into political power failed when his 1988 bid for the Republican presidential nomination fizzled, he still occupies an important place in the history of American religion and politics.

Along the way, he also helped spearhead the transformation of the Republican Party from an attitude towards Israel of indifference mixed with disdain to one of enthusiastic and devoted support.

But the majority of American Jews who were political liberals regarded his stands on issues like church-state separation, support for public-school prayer, as well as his opposition to abortion and sex education with fear and loathing. Jewish Democrats, even those who were supporters of Israel, put that issue far down on their priority list.

That antipathy was reinforced once Jewish audiences began to read about some of the hair-brained conspiracy theories that Robertson spread in his sermons and books. As Podhoretz noted, Robertson blamed “cosmopolitan, liberal, secular Jews” who want “unrestricted freedom for smut and pornography and the murder of the unborn,” and he has attacked them for their participation in the “ongoing attempt to undermine the public strength of Christianity.” Even worse, he often threatened “Jewish intellectuals and media activists” with “a Christian backlash of major proportions” in retaliation for the role they “played in the assault on Christianity” despite Christian support for Zionism.

There’s no way to characterize some of what Robertson said but as antisemitic. That was compounded by Robertson’s 1991 book “The New World Order” in which he accused Jewish bankers like the Rothschilds, Paul Warburg and Jacob Schiff (who were referred to as “Germans” rather than as “Jews”) of taking part in the conspiracy of the Illuminati and Freemasons to take over the world.

Robertson said he never intended any of this to be seen as antisemitic or as justifying hate against the Jews, writing: “I condemn and repudiate in the strongest terms those who would use such code words as a cover for anti-Semitism.”

The sort of language used by Robertson was highly reminiscent of the lunatic theories spread by hatemongers like Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. The denial of antisemitism was also consistent with the insincere claims of Jew-haters like Gore Vidal on the left, and Pat Buchanan and Joseph Sobran on the right that they weren’t antisemites.

Yet Podhoretz believed that Robertson deserved to be judged differently than those other figures.

As the famed writer put it, “In my view, Robertson’s support for Israel trumps the anti-Semitic pedigree of his ideas about the secret history of the dream of a new world order.”

No less a figure than former Anti-Defamation League national director Abe Foxman wrote in response to Podhoretz that “we do not believe Robertson to be anti-Semitic and did not argue that he is.” He went on to say that “one can air concerns about troubling statements and views without accusing their source of being an anti-Semite. With regard to Pat Robertson, that is precisely what the ADL’s religious Right report did — no more, no less.”

That was a bit of nuanced reasoning that confused a lot of Jewish liberals both then and now.

But while Robertson deserved to be criticized for what he said about Jews, as well as for spreading conspiracy theories, this still has to be balanced by behavior that set him apart from crude haters like Farrakhan, or more sophisticated antisemites like Vidal and Buchanan.

Robertson followed up his statements on Israel with actions that were redolent not just of affection for Zionism but for the rights of Jews. He was a loud and active supporter of the cause of freedom for Soviet Jewry. He donated millions of dollars to Jewish charities and causes, and inspired his followers to do the same. No one else accused of antisemitism has ever behaved in a similar manner. His devotion to Israel was heartfelt and expressed in a timely manner, demonstrating solidarity even at moments when standing with Israel was not politically popular, as during the Arab oil boycott in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War.

Counter-arguments made by cynical liberals don’t merit much consideration. Robertson had no ulterior motives, whether political or theological. Even if he and other evangelicals really did expect Jews to become Christians after the return of Jesus to Earth in messianic times (something that neither religious nor non-religious Jews believe is going to happen), the idea that this should scare or deter Jews from welcoming his support for Israel and Jewish causes is risible.

Yet the real sticking point with Robertson and his followers was something else: their stands on social issues on which they were polar opposites from liberal Jewry. And, if anything, those differences are even more stark now than they were in the 1990s when Foxman and the ADL seemed intent on going to war with the Christian right.

In part, that is because of events since then such as last year’s Supreme Court decision that overturned the Roe v. Wade precedent legalizing abortion, the fulfillment of a half-century of conservative activism. But while liberals still fear the power of conservative Christians, the truth is that the left’s capture of popular culture and much else has created a culture war in which it is the right and people of faith who are the ones who are on the defensive.

The dominance of the left in education, its embrace of sexual and transgender ideology and indoctrination, and efforts to treat those who don’t accept these ideas as outside the law has changed the political landscape.

The willingness to treat the right to worship as less important than the right to take part in Black Lives Matter protests during the height of the coronavirus pandemic was a turning point for many. That and the rest of the leftist dogma of critical race theory and its woke catechism of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) that is a recipe for a permanent race war has launched a culture war in which the right is only belatedly fighting back.

In this context, Robertson’s opposition to the liberal campaign to sweep the public square clean of religion must be seen as not so much an attack on Jews but as an effort to defend the rights of all people of faith.

Robertson’s troubling statements about Jews should never be rationalized, any more than we should tolerate instances when those who have done great things for Israel — like former President Donald Trump — then embrace antisemites. But at a time when left-wing antisemitism is on the rise, Robertson’s peculiar blend of odd theories about Jews and ardent love for Israel needs to be understood as not presenting any sort of threat to Jewish life.

As anti-Israel and anti-Zionist invective and activism in the form of the BDS movement and incitement (such as last month’s graduation speech at CUNY law school) increases, the Christian conservative movement that Pat Robertson helped found is the Jews most dependable ally. It ill behooves those on the left who look to a Biden administration that has embraced a toxic DEI agenda that grants a permission slip for antisemitism to defend Jews to at the same time regard friends like Robertson’s followers with suspicion and disdain.

Those who might bash Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu or AIPAC for mourning his passing because of the awful stuff Robertson said are missing the point.

Robertson was a flawed and problematic friend, yet his activism for Israel — and that of others he helped inspire on the Christian right — altered the political correlation of forces in this country in a way that did more good for the Jews than that of virtually any other person. In a world in which the Jews still have many powerful enemies, that ought to be enough for us to characterize the television preacher as someone who deserves to be remembered with far more gratitude than criticism.

51.0°,

Overcast

51.0°,

Overcast