Q and A with Robert Alter

Posted

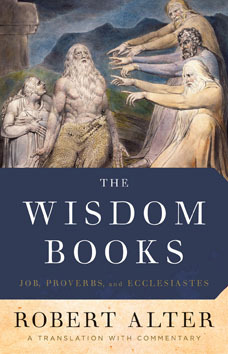

Issue of September 22, 14 Tishrei 5771Robert Alter is one of the foremost secular translators of the Bible. His newest work, “The Wisdom Books,” is a new translation of Mishei (Proverbs), Koheles (Ecclesiastes), and Iyov (Job). Michael Orbach: Why are the translations titled “The Wisdom Books?” Robert Alter: This is not a label intrinsic to the Bible. Modern scholars have figured out that throughout the Ancient Near East, Mesopotamia and Israel, there was an activity called wisdom, in Hebrew ‘chochma.’ In many places there is evidence of actual schools where wisdom was taught. These were the texts that came down to us from the wisdom activities; texts that deal with how you lead the right life and questions of whether there is justice in the world, both practical and some of it verges on philosophical. It has no national content — it really is universal. In the Bible the three books that clearly seem to belong to this activity of wisdom writing and wisdom thinking are these three. MO: How does that jibe with our traditional understandings of the text? RA: Traditionally, as far as Job goes, the Talmud says that Job was a parable. The Talmud itself recognizes that Job doesn’t report historical facts. Of course, Jewish tradition attributes both Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, Koheles, to King Solomon. There was a general practice to assigning new books to figures in the national past who were very important. What I can say is this: if you just look at the language, earlier Biblical Hebrew like any other language evolved over time. We no longer use English quite the way that Shakespeare did, even though we can, more or less, understand Shakespeare. We’ll miss certain phrases. In all three of these books, you see smoking gun evidence that they were written after the Babylonian exile; certain words that never appear in Biblical Hebrew appear. Certain grammatical forms that were not used are used. Let me correct that for Proverbs: Proverbs is an anthology of wisdom sayings and it spans quite a few centuries and is quite different. Especially with Job and Koheles, you see earmarks of a later era. One particular piece of evidence, by the time of the return of the Babylonian exile, Aramaic was beginning to replace Hebrew as the spoken language of the people of Judea, it was a serious competitor to Hebrew. What you find in Job and to a lesser degree in Koheles are a lot of words borrowed from Aramaic, which you would never find in the Torah. MO: What is it like translating these texts? RA: I find it exciting. At times, it’s a very daunting challenge. Let me cite that especially in relation to Job, because the poetry of Job is astonishingly great. It’s like Shakespeare’s poetry in King Lear, it takes your breath away. Since poetry depends on the particular words used and the music of the words and their association this is very hard to convey in another language. You always have a sense you’re climbing up Mount Everest, but it’s also exciting because sometimes, while you never totally get it, you feel that you almost get it and there’s a sense of exhilaration. These are books that have been translated many times by Jews, Catholics, Protestants, especially Protestants in English. I’m not discounting the previous translations, each one has its own merits, as well as its own problems. No one would set out to translate any work, Biblical or otherwise, unless he or she felt that there was something inadequate about the existing translation. I feel most of all the existing translations don’t really get very close to the compact power and energy and directness of the Hebrew. In a way, as a translator, I try to scrape away pre-conceived notions of what the text sounds like in English and to get at an English that is closer to the contours and even the rhythms of the Hebrew. MO: Do you use any translations? RA: I do my best to not look at any other translation while I’m working on my own. Once I’m finished with a draft I’ll look at two or three sometimes for translation. Occasionally, it’s the exception rather than the rule, on a level of a single word choice, I’ll say ‘Hey they had a better idea than I had,’ and I’ll use that word instead of my own. The two translations I look at most frequently are the new Jewish Publication Society (JPS) translation, which is the one that I think has had the most currency over the last quarter century among Jewish readers. I’m increasingly dissatisfied with the new JPS translation; they have a wretched sense of English style. The style in the Hebrew in just about all the books of the Bible is extraordinary, when you translate this into an English that sounds vaguely like a mixture of the daily newspaper and the bureaucratic directives, you’re doing serious violence to the Bible. The other translation that I look at the King James Version and that has its problems. Christian Hebrew scholars at the beginning of the 17th Century did not understand Hebrew nearly as well as we do today, or nearly as well as scholarly Jews did. If you compare the understanding of the Hebrew of Ibn Ezra or Rashi to the King James translators there’s no contest. There are a lot of errors, some of them are real howlers and there are small errors all along. In some of the books, not so much in the narrative books, but psalms, there are a lot of terms that really reflect later Christian theology like salvation for a Hebrew word that means rescue, soul for a Hebrew word that means life or life’s breath. Those are problems with the King James version and some of the language has become archaic, but having said that, those 17th century translators have a wonderful sense of English style.

Report an inappropriate comment

Comments

45.0°,

Partly Cloudy

45.0°,

Partly Cloudy