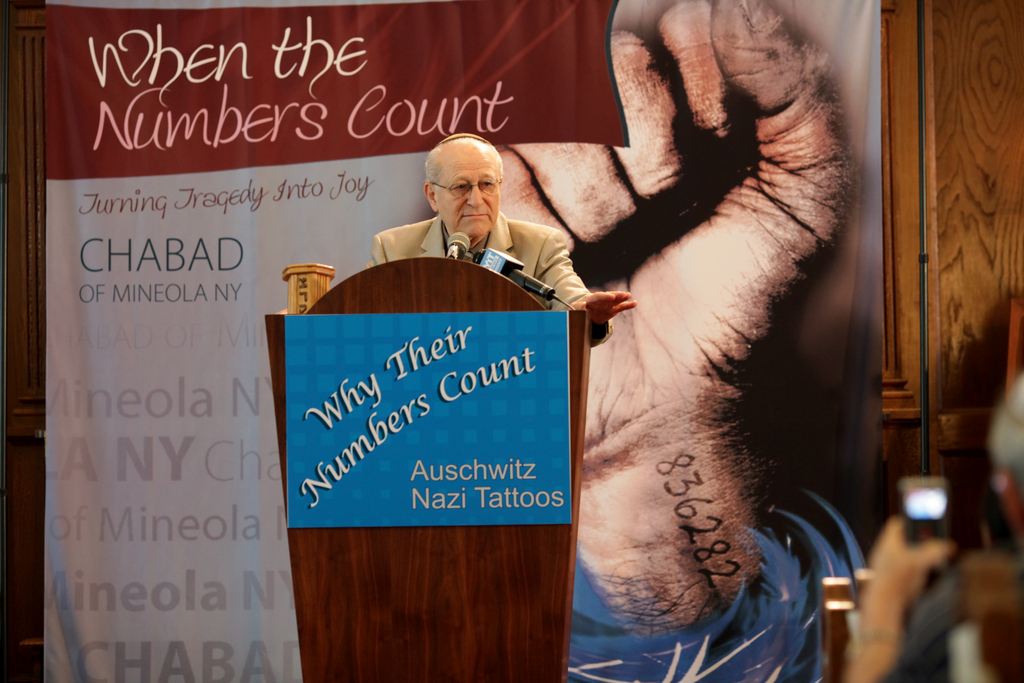

Badges of honor: Survivors’ tattoos displayed, honored at Chabad event marking an Auschwitz anniversary.

For a year and a half, Zelik Sander was known by the tattooed numbers on his arm. His wife, Sally, also a Holocaust survivor, was ashamed of the numbers on her arm.

“Someone told my wife that only a prostitute is tattooed," said Sander, who lives in Port Washington. "She broke down, went to a psychiatrist, and had surgery to remove it. I covered mine for 30 years.”

Sander's tattooed arm was not covered on Wednesday, June 30, in an event organized by the Chabad of Mineola. Sander and several other Holocaust survivors came to celebrate their tattoos.

“I never though about it until I got this invitation,” said Sander. In the Auschwitz death camp where Sander and his wife were inmates, Sanders said, he didn't think much of it. “The hunger took hold of the pain. For 19 months, I was called by my number and had to respond.”

While Jewish law forbids tattoos, Rabbi Anchelle Perl, rabbi of the Chabad of Mineola, said that Holocaust survivors stand in a separate category.

“They should be worn as a badge of honor, this kind of tattoo could be a reminder to the world,” said Rabbi Perl, who also spoke of a recent case in Israel. In 2008, Ron Folman, a son of Holocaust survivors, asked a tattoo artist to make him an exact copy of the number his father had on his arm. His father initially refused to cooperate, but later accompanied his son to the tattoo parlor.

Rabbi Perl disagreed with Folman’s tribute, though not with the idea behind it.

“I urge you not to have a tattoo,” Rabbi Perl told the audience. “There are other ways to not be forgotten.”

Jack Rosenthal, a Holocaust survivor who lives in Roslyn, spoke about how he managed to survive the camps.

“The reason I survived is because I had a religious background, and I had bitachon (faith) that I would come out of there alive,” said Rosenthal.

He never really thought about the tattoo itself until he had a visit from a plumber who saw his numbers.

“The repairman could not believe that I was one of the camp survivors," Rosenthal said. "He gave me a... faucet for free.”

Rosenthal said that after a visit to Williamsburg, he was told that the Satmar and Vizhnitz Rebbes considered the blessing of a tattooed religious survivor to be as good as the blessing of any rabbi.

Alongside the survivors, Stella K. Abraham High School student Deborah Watman spoke about her grandparents’ survival.

“Hundreds of God-fearing Jews will claim descent to my grandparents,” said Watman.

Speaking of a Nazi plan to build a museum for the exterminated Jews, Watman sounded a note of irony. “We are the ones who look upon German actions on display," she said. "Not the other way around.”

The date of the commemoration was chosen to mark June 30, 1942, the day when the second gas chamber began operating at Auschwitz. Rabbi Perl said this year's anniversary also coincided with a positive Hebrew date.

“Today, June 30 is Tammuz 18,” said Rabbi Perl. “18 is chai, which is life.”

In the audience were 36 campers from the Ruach Day Camp in Uniondale.

“It’s very important to get an education, because they’re the next generation,” said Camp Director Lynda Last.

“It behooves our young generations to witness the stories of survivors and become live witnesses,” said Rabbi Perl. “Despite what they went through, they responded positively.”

Irving Roth, a survivor born in Slovakia was pleased with the turnout, which filled the synagogue and included media coverage from local news stations. “The number of survivors is limited, and people are listening,” said Roth.

Rabbi Perl directly confronted the question of faith in light of the Holocaust. For the last Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Rabbi Perl said, the events only reaffirmed his faith.

“The Rebbe would say ‘On the contrary, the Holocaust has disproven any possible faith in a human-based morality,’” said Perl. Instead, he said, it was faith in G-d that was reinforced for the survivors.

“They have a neshama that was never touched,” Rabbi Perl explained, using the Hebrew term for soul. “They show that despite what was imprinted on them, their neshama was always engraved in them.”

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair