Iranian diplomat honored at Nassau Holocaust Center

A wartime diplomat dubbed the “Iranian Schindler” was honored by the Nassau Memorial & Tolerance Center as part of a larger effort to raise awareness of its work in the local Persian community.

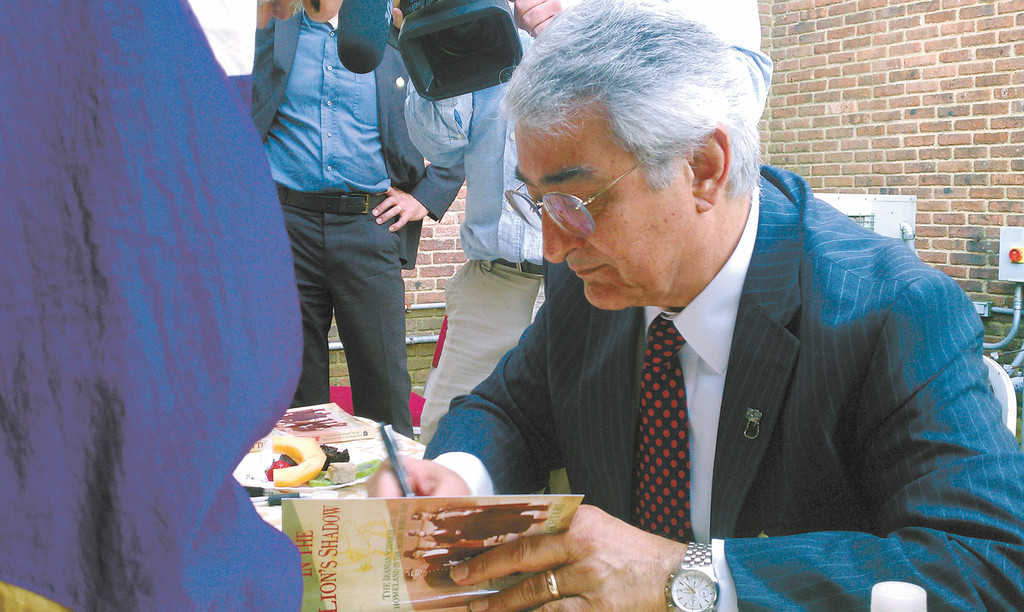

On Sunday, the center hosted Dr. Fariborz Mokhtari, author of a book on Abdol-Hossein Sardari, the junior envoy who saved hundreds of Jews in Nazi-occupied France by issuing Iranian passports and convincing Nazi officials that Persian Jews were racially Aryans who happened to be practicing Judaism. “The Iran in which I grew up was tolerant. I heard stories of Iranians helping Jews during the Second World War and I wanted proof,” Mokhtari said.

Mokhtari immigrated to the United States during the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and teaches at National Defense University in Washington. He began his research on Sardari at the National Archives and then tracked down individuals rescued by Sardari, as well as members of the diplomat’s family. “He cultivated relations with Nazi and Vichy officials,” Mokhtari said. “He knew that the Nazis had based their policy on the dubious notion of blood and Iranians who practiced Judaism were Aryans who were following the prophet Moses.”

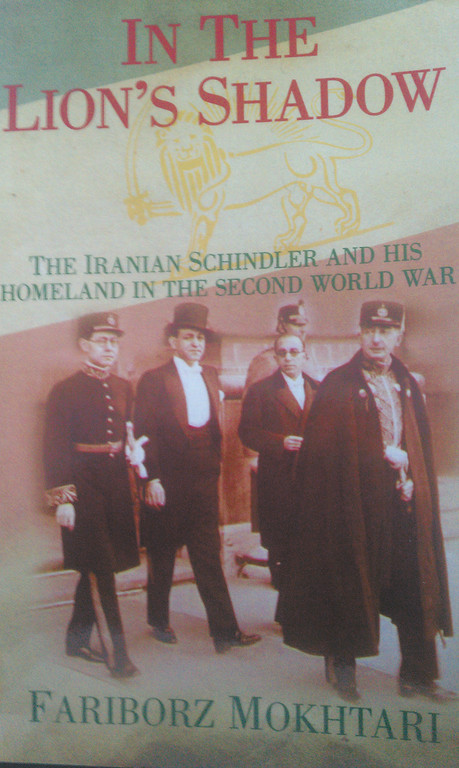

Mokhtari’s biography of Sardari, “In the Lion’s Shadow,” published by The History Press in 2011, connects the diplomat to a centuries-long tradition of tolerance in Iran, reaching back to Cyrus, who issued a proclamation on a clay cylinder providing religious tolerance following his conquest of Babylon. A replica of the Cyrus Cylinder from the British Museum is on display at the Holocaust center.

Although only 150 Iranian Jews had resided in Paris at the time of the Nazi invasion, the city’s Jewish population also included Jews from Central Asia and the Caucasus. Partnering with Ibrahim Morady and Dr. Asaf Atchildi, a Bukharian Jew and community leader, Sardari submitted documents to Nazi officials testifying that Central Asian Jews were actually the Jugutis, a made-up term that described Persians who practiced the “Mosaic” faith. Deprived of his income, Sardari remained in Paris and issued somewhere between 500 and 1,000 blank Persian passports to other local Jews facing deportation, including Ashkenazim.

Like other neutral diplomats, he risked his career. Sardari applied to Yad Vashem in April 1978 for recognition, but because his life was not at risk, he did not receive the same honor as Oskar Schindler, among other Righteous Gentiles listed by the Israeli Holocaust memorial center. Following the Islamic Revolution, Sardari was denied pension and his properties in Iran were confiscated. He died in London in 1981.

Alongside the lecture, a special exhibit on Sardari displayed objects loaned by relatives of Sardari, and the Senehi, Cohanim and Mikaeloff families, whose relatives were rescued during the war.

Among the museum’s supporters, Great Neck lawyer Sean Sabeti, a Muslim who immigrated during the revolution, said that the exhibit serves to show that there was once an Iran that tolerated other faiths. “Ahmadinejad used devilish words on the Holocaust and I was very disturbed. I took it upon myself to educate people,” Sabeti said. “The idea is to bring in more Persian Americans, not just Jews, and show what happened during the war.”

The lecture and exhibit was attended by local Persian Jewish activists, including artist Josephine Mairzadeh, who contributed a painting for an exhibit accompanying the lecture. Her portrait highlights Norooz, the Persian New Year holiday. “It’s a transparent holiday celebration by Zoroastrians, Muslims and Jews, it encompasses all peoples of Iran,” Mairzadeh said.

In contrast to other local Holocaust memorial events, which sometimes feature representatives from the German, Polish or other European governments, no Iranian officials were invited to the lecture.

Jericho resident Cheryl Garber described Sardari’s use of Nazi racial doctrine as “brilliant and brave,” and praised Mokhtari’s book. “Every page is full of history and shows that the Holocaust affected so many cultures,” noted Garber.

The exhibit “Iranian Schindler” runs until December. For more information, visit holocaust-nassau.org

68.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

68.0°,

Mostly Cloudy