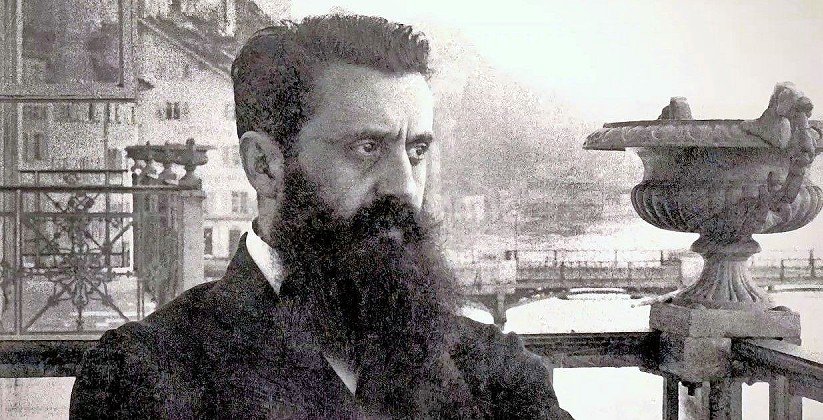

Haunted by Jew-hatred, like most European Jews

This is our third excerpt from the new three-volume set, “Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings,” the inaugural publication of The Library of the Jewish People edited by Gil Troy.

In 1866, a young Theodor Herzl enrolled in a Pest Jewish Community primary school, the Pester Israelitische Normalhauptschule. Four years later, he moved to Pest’s Technical School, the Realschule, remaining for the next five years. By 1876, he would be attending a Protestant high school, Evangelische Gymnasium. Along the way, on May 3, 1873, Herzl had a confirmation or bar mitzvah — it remains unclear how Jewishly rich it was or how Jewishly literate he ended up being.

Much of Herzl’s adolescent identity crisis was of the usual, bourgeois, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” variety. In 1874, when he founded the “Wir” (We) literary society, he turned from technical studies toward the literary passions that would define his professional life. He was also snarled in a typically Austro-Hungarian dilemma about linguistic identity, apparently switching back and forth between the Magyar and German languages effortlessly. It is significant that Herzl lived in the unstable Austro-Hungarian Empire, with its patchwork quilt identities, as opposed to more monolithic countries such as Germany and France.

Herzl would recall encountering Jew-hatred from students and teachers in his overwhelmingly Hungarian technical school. Despite its name, the Protestant high school was filled with Jews like the Herzls, trying to fit in, unhappy standing out, but still consciously, somewhat proudly, Jewish.

Then, in 1878, weeks before turning 18, Herzl endured the greatest — and most uprooting — tragedy of his life. His only sibling, his beloved older sister by one year, Pauline, died of typhoid fever days after contracting it. Within a week, the family settled a longstanding debate and moved to Vienna, into an overwhelmingly German-Jewish milieu. This move rushed Herzl away from hard memories, but wrested him away from comforting evocations of his sister, too.

Still grieving, Herzl studied law at the University of Vienna. His choice was practical, ambitious, conventional. While working his way to graduating with a doctorate in law in 1884, he indulged his real passion: writing comedies, essays, poems.

In 1894, watching the French novelist and nationalist parliamentarian Maurice Barrès become increasingly right-wing and aggressive, Herzl would sneer that the “political mendacities of Barrès the politician have effectively killed the artist in him.” Revealing a long-term struggle he resolved in the opposite way, Herzl would conclude that “any ‘artist-politician’ who attempted to make art serve the rebellion against that legal culture, such as Barrès, was in effect committing moral, and hence artistic, suicide.”

• • •

Embracing his German identity, fascinated by the romantic nationalist currents sweeping Europe, Herzl joined the Akademische Lesehalle, a non-partisan student cultural association, shortly after enrolling at the university. In 1880, he joined the German nationalist fraternity, the Akademische Burschenschaft Albia. Both organizational affiliations ended badly — because German nationalism was becoming increasingly addicted to Jew-hatred while morphing into a new, totalitarian, race-based ideology hostile to assimilating outsiders.

Shortly after a memorial for the Jew-hating German national composer Richard Wagner, which included a representative of Albia joining in a chorus of anti-Semitic speeches, Herzl threatened to resign. To his shock, his mates accepted his resignation. Even worse, no other Jews joined his protest.

This growing scourge of Jew-hatred burdened Herzl. In 1882, he read Wilhelm Jensen’s account of fourteenth-century Jew-hatred, “The Jews of Cologne.” He also read Eugen Dühring’s depressingly popular 1881 anti-Jewish screed, “The Jewish Problem as a Problem of Race, Morals and Culture.” Dühring found the Jewish presence so cancerous it had to be removed. Herzl would say that reading it was like getting “a smack” on the head. He started seeing Jew-hatred as endemic to the European character.

Much of the Jew-hatred Herzl witnessed was intellectual and ideological. Occasionally it was personal.

In 1888, as he left a pub in Mainz, someone called out “Hep, hep,” the chilling Crusader cry “Hierosolyma est Perdita” [Jerusalem is lost], which inspired German anti-Jewish riots in 1819. One shout led to another, as others in the crowd mocked this proud man — and his Jewish looks. Another time, Herzl would recall, “Someone shouted ‘Dirty Jew’ at me as I was riding by in a carriage.”

Herzl often showed more spine than his peers. He would recall “as a green young writer” being advised “to adopt a pen name less Jewish than my own. I flatly refused, saying that I wanted to continue to bear the name of my father.” Herzl “offered to withdraw the manuscript.” The editor caved.

Early on, when he was still trying to fit in, there were clear signs that the Theodor Herzl that always was — was the Theodor Herzl he eventually became.

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy