Chana Nachenberg: Ahlam Tamimi’s 16th victim

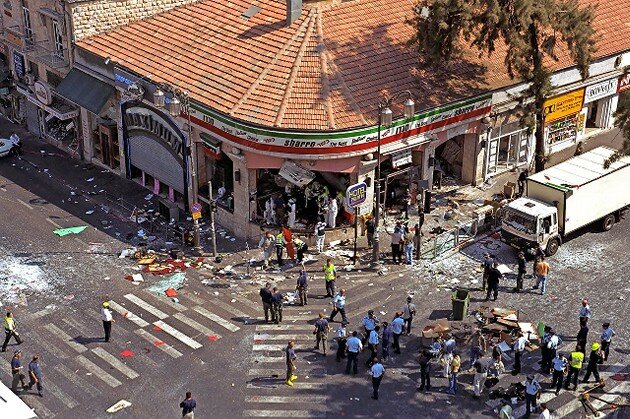

Twenty-two years after a Palestinian suicide bomber devastated the Sbarro pizza restaurant in downtown Jerusalem, the 16th victim of that massacre succumbed to her injuries.

Chana Nachenberg, an American-Israeli mother who was 31 at the time of the deadly attack in August 2001, died on May 31, having never woken from the coma in which she languished for so long after the bombing.

“After almost 22 years of heroism, Chana is the 16th victim of the attack,” her father, Yitzhak, said prior to her funeral in the central city of Modi’in on Thursday morning.

Nachenberg’s is not the only harrowing experience recorded on that terrible day, Aug. 9, 2001, which came during a spate of suicide bombings against Israeli targets carried out by Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Fatah and other Palestinian factions. Yet arguably more disturbing than the stories of those who lost their lives and the more than 100 who were injured is the simple fact that justice continues to be denied.

Thanks in part to the advocacy efforts of Arnold and Frimet Roth, whose 15-year-old daughter Malki, an American citizen, was also murdered at the Sbarro restaurant, the facts of the bombing are fairly well known, as is the identity of the accomplice of the terrorist, Izz al-Din Shuheil al-Masri, who died executing the atrocity.

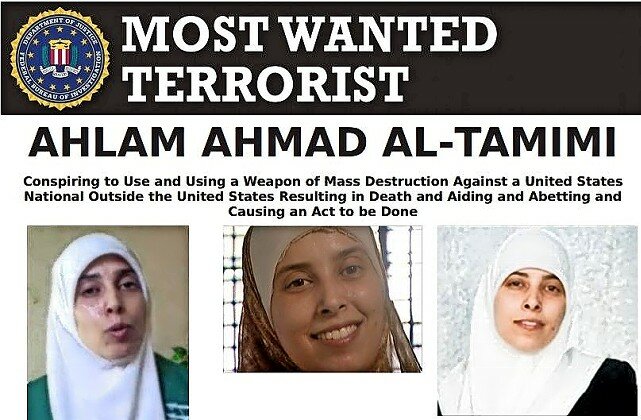

Al-Masri was driven to the pizzeria by a Jordanian-born Palestinian woman, Ahlam Tamimi, who also assisted with the preparation of his bomb. Tamimi was apprehended by Israeli security forces following the atrocity and sentenced to 16 consecutive life terms in prison.

In October 2011, as part of the deal in which 1,027 Palestinian prisoners were exchanged for Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier who spent more than five years in Hamas captivity, Tamimi walked free. Moving to her native Jordan, Tamimi became a celebrity in the Arab world, hosting her own weekly show on the Hamas satellite TV station, Al Quds. In between extolling the virtues of “martyrdom attacks” against Jews, she frequently celebrated her own monstrous achievement. On one occasion, when Tamimi learned that she had enabled the killing of eight children at the Sbarro restaurant and not three as she had previously believed, she turned to the camera wearing a broad grin of pride.

It was not until 2016, five years after Tamimi’s release, that a glimmer of hope concerning her possible arrest came into view when the US Department of Justice issued a warrant for her capture. However, an American attempt to extradite her in 2017 was rebuffed by the Jordanians, who by disingenuously claimed that a bilateral extradition treaty that was agreed with the United States more than 20 years earlier had expired.

The American understanding is that the treaty remains in force and that justice for US citizens murdered in terrorist attacks, like Malki Roth, is of the highest priority. Still, the Jordanians continue thumbing their noses in Washington’s direction in the case of Tamimi.

One might argue that this wretched situation would be much simpler had Tamimi moved to Iran instead of Jordan. Were Tamimi ensconced in Tehran — a capital city with no American or Israeli embassies, where diplomats representing democratic countries are closely monitored by the Iranian regime — there would be little prospect of securing her extradition.

Still, that would at least allow both American and Israeli government representatives to denounce the ruling mullahs for harboring a convicted terrorist, as well as for their ongoing commitment to terrorist organizations that are sworn to the Jewish state’s destruction, without worrying about any diplomatic fallout.

But Jordan is different, for both the Israelis and the Americans. Israel is reluctant to press the Jordanians to re-arrest an individual it previously released, fearing that its delicate relations with the Hashemite Kingdom might be weakened even more through such a request. Additionally, now that Tamimi is the focus of a US warrant, Israel can argue that this is a matter for Amman and Washington alone.

Similarly, America is reticent about landing too many demands at the door of Jordan’s King Abdullah, regarded as a critical strategic partner in the Middle East. “The United States and Jordan share an enduring, strategic relationship deeply rooted in shared interests and values,” US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a statement marking the 77th anniversary of Jordanian independence on May 25. “We appreciate the important role Jordan plays in promoting peace and security across the region and countering violent extremism.”

Plenty of praise, then, for Jordan’s position as a pro-Western state opposing Islamist groups in the region, but no mention of Tamimi, who was similarly absent from a conversation that Blinken held earlier in May with his Jordanian counterpart, Ayman Safadi. That discussion concentrated in the main on Syria, where Jordan — once a participant in the international coalition opposing President Bashar Assad — is now bolstering that bloodstained regime.

Notably, Blinken did not criticize Jordan’s change of position, stating only that the United States would not normalize relations with the Middle East’s last remaining Ba’ath Party dictatorship until all parties accept a UN-sponsored political process. In approaching the Jordanians with kid gloves on the Syrian issue, as well as on Tamimi’s extradition, Blinken is essentially saying that persuasion, not compulsion, is the way forward.

Several members of Congress on both sides of the aisle clearly do not agree. At a hearing in early May on the nomination of Yael Lempert as the US Ambassador to Jordan, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) suggested that aid to Jordan might be suspended if the kingdom continues to refuse Tamimi’s extradition. “We need to use every tool we have. And I have no desire to cut off aid to Jordan,” Cruz told Lempert. “What I desire is to get this terrorist who murdered Americans to face justice.”

Lempert was clearly unnerved by Cruz’s remarks. “I think that that would need to be weighed very carefully against the range of issues and priorities that we have with the Jordanians before considering such a step, which I think would be profound,” she responded, expressing what anyone who speaks diplomatese would understand as a “no.”

She then added: “I think that what I can confirm to you is that I will do everything in my power to ensure that Ahlam Tamimi faces justice in the United States.”

The intention is there, but, frankly, the power Lempert referred to is not. Right now, the United States is relying on Jordanian goodwill when it comes to Tamimi’s extradition, but within the “range of issues and priorities” mentioned by Lempert, that goal ranks depressingly low.

As Israel mourns another victim of terrorist violence whose life was effectively ended by the bomb that Tamimi enabled, justice — as a result of Jordanian intransigence, and Israeli and American indulgence of that intransigence — remains elusive.

50.0°,

Overcast

50.0°,

Overcast