Beyond 9 Days, brisket wasn’t on the table

Last month, tens of thousands of people descended on Tel Aviv’s Sarona Park to sample seitan, sprouts and seaweed. Vegan Fest, the largest gathering of its kind in the world, reconfirmed Israel’s status as the Vegan Nation, with more than 5 percent of the Israeli population avoiding meat and dairy.

But in the Diaspora, Jews are not known as the “People of Alternative Protein.” On the contrary, Ashkenazi cuisine, the dominant conception of Jewish food in America, is a panoply of animal products, from towering corned-beef sandwiches to chicken soup to cheesecake.

For these nine days, however, observant Jews embrace an alternative diet, abstaining from meat, poultry and wine on weekdays, an expression of mourning for the destruction of the two Temples in Jerusalem and other calamities.

While the custom is often framed as an onerous burden (“What will we make for dinner?”), a closer look at the history of meat consumption in Jewish tradition reveals a surprisingly complex and fluid story, one that a new generation of Jewish chefs is telling with pride.

The story begins in the first chapter of Genesis when G-d commands Adam to eat only “seedbearing plants … and fruits,” in other words, to be vegetarian. Permission to eat meat is granted only later, to Noah after the flood, and then only as a grudging concession to human appetites.

“The biblical view of meat consumption is surprising to the uninitiated,” says Yitzhaq Feder, a lecturer in biblical studies at the University of Haifa. “Generally, it is part of a sacrifice in which portions were burned on the altar or given to the priests, and the remainder was consumed by the family who brought the offering.”

In fact, a less well-known verse in Leviticus (17:4) actually prohibits the consumption of meat outside of a sacrificial setting, comparing it to murder. Though this prohibition is relaxed in Deuteronomy, there is clearly some ambivalence within the text about how much meat people should eat, and when and where they should eat it.

“Meat was always a part of celebration, especially of festivals, in ancient Israel,” says Feder. “It is important to keep in mind that meat was a much rarer commodity, and the raising of livestock was much closer to home (at least in comparison to urban populations today). The custom of not eating meat during the Nine Days is based on the assumption that such meals were noteworthy events.”

After the destruction of the holy Temple, rabbinic literature preserved the special status accorded to meat by marking it as a delicacy, a way of honoring the Shabbat and festivals. Kabbalists like Rabbi Isaac Luria opined that meat should be eaten only with high spiritual intentions, and the economic status of most Diaspora Jews ensured that it was not the stuff of weeknight dinners.

“Jews in Eastern Europe did not have access to a lot of meat,” says Nora Rubel, professor of Jewish studies at the University of Rochester and editor of the 2014 anthology “Religion, Food and Eating in North America.” Complicated kosher laws, she notes, made it even more expensive and difficult to procure. “For the holidays, they would scrimp and save to be able to eat like rich people.”

Dishes like gefilte fish, chicken soup and chopped liver were designed to make small, cheap cuts of meat go a long way. But in tandem with these, Eastern European Jews developed a bright and varied array of plant-based foods. The salads, soups, pickles and krauts they made with the cruciferous vegetables plentiful in that region were codified in the 1938 Yiddish classic “The Vilna Vegetarian Cookbook.”

It was only in 19th- and 20th- century America that meat became a staple of the Jewish diet. Industrial practices like giant feed lots and refrigerated railway cars made it affordable enough to eat every day, notes Jeffrey Yoskowitz, a Jewish food expert and founder of Papaya, a delivery platform that encourages restaurants and diners to serve and consume less meat.

“What once was revered and saved for special occasions was suddenly available all the time. It was so cheap in America that delis stacked meat so high on a sandwich, and it became a symbol of American Judaism.”

Yoskowitz and Rubel, who, with her husband, runs Grass Fed — a kosher vegan “butcher” in Rochester — are looking to revive the more varied, less meat-centric cuisine of their ancestors.

“Vegetarianism (or meat reductionism) has been a part of global Jewish culture for most of our history,” says Yoskowitz, whose 2016 cookbook, “The Gefilte Manifesto,” presents a modern take on traditional Ashkenazi fare.

The custom of abstaining from meat during the Nine Days provides a chance to explore this traditional way of eating and an opportunity to reflect on its deeper significance.

“There are a lot of tragedies that we don’t have the power to stop,” says Rubel. “There are very few things we can do in our daily lives to alleviate the suffering of others. This is one of them.”

Hungarian Braised Green Cabbage (Pareve or Dairy)

From “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Food” by Gil Marks. Serves 6 to 8.

Ingredients:

2 lb. (1 medium head) green or Savoy cabbage, cored and coarsely shredded

1 tsp. salt

1/4 cup butter or vegetable oil

1 large yellow onion, chopped

About 1 cup water or broth, or ½ cup dry white wine and ½ cup water

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

1 lb. cooked pasta or wide egg noodles

Directions:

Sprinkle the cabbage with salt. Let stand for 1 hour. Drain and squeeze out the excess liquid. In a large skillet or pot, heat the butter or oil over medium heat. Add the onion and sauté until soft and translucent, 5 to 10 minutes.

Add the cabbage and sauté until reduced and slightly wilted, about 3 minutes.

Add enough water to prevent the cabbage from sticking. Add the salt and pepper. Bring to a boil, cover and reduce heat to medium-low, and simmer until tender but still slightly crunchy, about 20 minutes. Add the noodles and heat through, about 5 minutes. Serve warm.

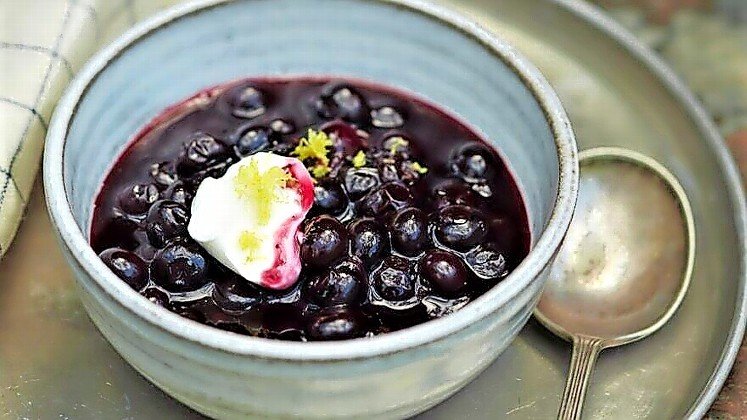

Spiced Blueberry Soup (Dairy)

From “The Gefilte Manifesto” by Jeffrey Yoskowitz and Liz Alpern. Serves 4 to 6.

Ingredients:

2 cinnamon sticks

2 tsp. whole cloves

1 Tbsp. coriander seeds

2 tsp. whole black peppercorns

6 cups fresh or frozen blueberries

1/4 cup honey

1/4 cup fresh lemon juice

1 cup cold water

2 egg yolks, lightly beaten

2 tsp. lemon zest, plus more for garnish

Sour cream or plain yogurt, for serving

Directions:

Tie the cinnamon sticks, cloves, coriander seeds and peppercorns in a square of cheesecloth for easy removal later.

In a medium saucepan, combine the blueberries, honey, lemon juice, spice bundle and cold water. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat, then reduce the heat to maintain a simmer and cook for about 8 minutes. The berries will break down quite quickly and release a good deal of liquid.

Remove the pot from the heat. Very slowly spoon 3 Tbsp. of the hot blueberry liquid into the egg yolks (1 Tbsp. at a time to avoid curdling the egg yolks). Whisk with a fork until thick, 1 to 2 minutes, then return the blueberry-egg mixture to the pot and return the soup just to a boil.

Immediately reduce the heat to maintain a simmer and cook for 3 minutes more, until the soup has thickened. Remove from the heat, and immediately mix in the 2 tsp. of lemon zest.

Remove the spice bundle before serving the dish hot, cold or at room temperature, garnished with sour cream and remaining lemon zest.

49.0°,

Fair

49.0°,

Fair