Vindman’s shameful vilification by fellow Jews

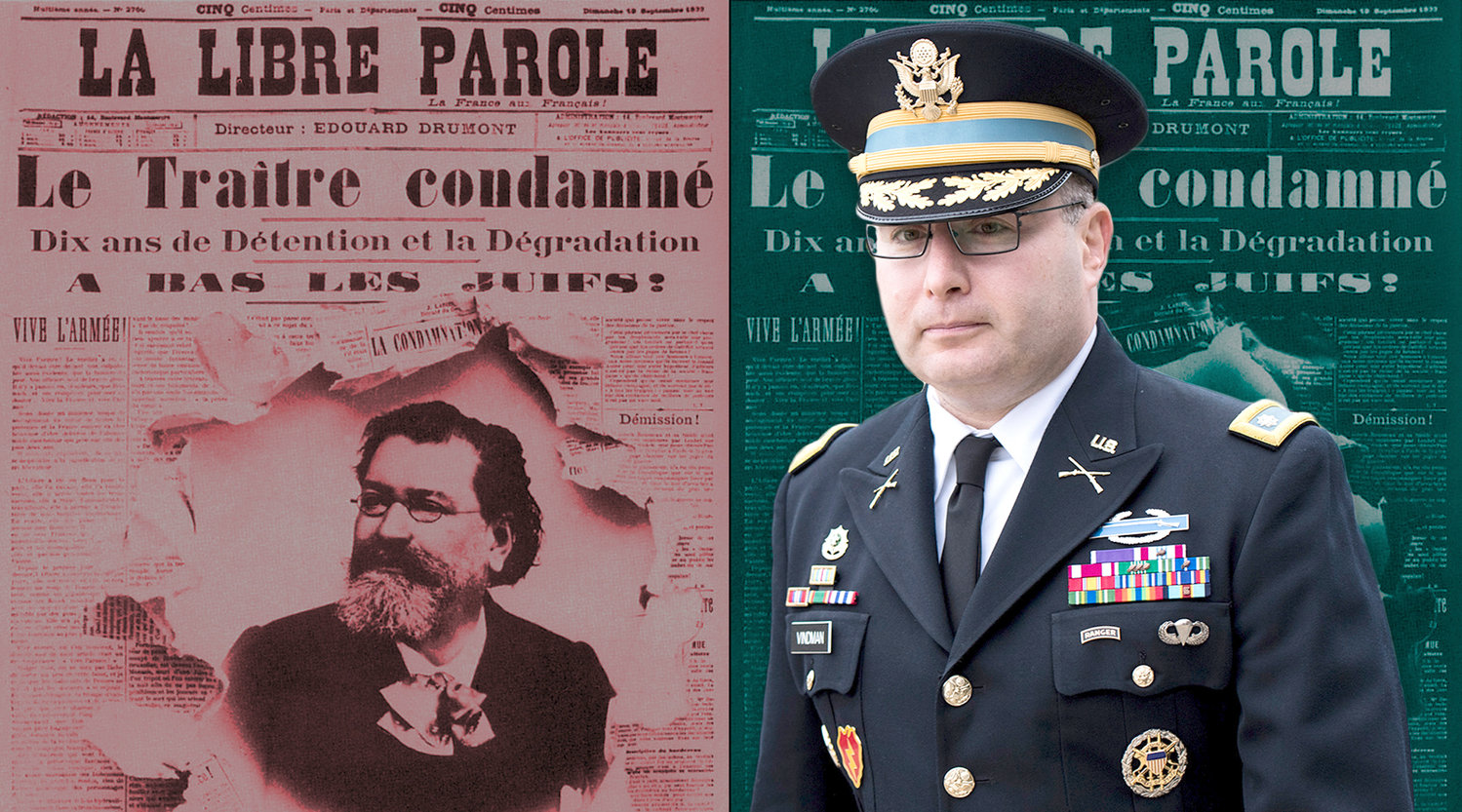

On Jan. 13, 1898, the French novelist Emile Zola published an open letter titled “J’Accuse!” in which he called out the anti-Semitism of the French government and France’s military establishment.

Zola demanded justice for Capt. Alfred Dreyfus, a Frenchman of Jewish descent who was accused by the military of being a German spy, and subsequently suffered imprisonment and public humiliation. Throughout the so-called Dreyfus Affair, the French public remained split between those who believed in the captain’s honor and honesty and those who stuck to the age-old prejudice that a Jew can never be trusted, especially on matters of national security.

Suspicions of dual loyalty and treachery have followed the Jews over the centuries along the path of their migration and exile, from North Africa to Spain, from Spain to France and Germany, from Germany to the Russian Empire and beyond.

Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman is a naturalized U.S. citizen, whose family emigrated from the Soviet Union when he was still a toddler. A decorated army veteran and White House official, he was one of the aides listening in on President Donald Trump’s phone call with Volodymyr Zelensky, in which Trump asked the Ukrainian president to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden. And now, as a result of his congressional testimony, Vindman enjoys the dubious distinction of being just the latest Jew to be accused of dual loyalty by political enemies.

In an Oct. 28 Fox News panel, host Laura Ingraham and guest John Yoo launched into a freewheeling attack on Vindman, entertaining the idea that he could be guilty of espionage. On Oct. 29, former GOP Rep. Sean Duffy told CNN’s John Berman that Vindman seems to be more concerned with Ukraine’s military defense than with America’s foreign policy interests.

Many Democrats and Republicans swiftly and strongly spoke out against this vilification of an American patriot. But as praiseworthy as these condemnations were, Jewish Americans — regardless of their political affiliations — should understand the added danger of the smear campaign against Vindman: It not only represents an attack against immigrants, but fuels contemporary anti-Semites looking to breathe new life into tropes of Jewish dual loyalty.

In April 1945, my great-uncle, Aaron, a Red Army colonel, led his artillery division in the storming of Berlin. After the triumphant battle, most of the participating colonels were promoted to the rank of general. Aaron was denied the promotion because he was Jewish. Jewish generals were a rarity in the postwar Soviet military — Jews could not be trusted.

At the height of Stalin’s postwar anti-Semitic campaign and on the eve of the infamous “Doctors’ Plot,” my father, a young aspiring engineer, was suddenly fired from his job and denied employment until after the tyrant’s death; his duties were deemed too sensitive to be trusted to a Jew. He barely survived on his tiny disability pension and the experience, which included an expectation of imminent arrest, scarred him for life.

My own experiences during the waning years of the Soviet empire were far less dramatic, but the feeling of being an outsider, someone whose loyalty could be questioned and right to belong revoked, was certainly part of it. I’ll never forget passing the newspaper stands on my daily walks to and from school. The newspapers decried the evils of Zionism and depicted nefarious-looking hook-nosed creatures who were plotting to spoil the party of “progress-loving humanity.” The creatures’ noses looked like mine.

Hundreds of thousands of Soviet Jews arrived in the United States during the Soviet Union’s last two decades, and it seems fair to suggest that most of them liked what they found in this country. They were now free to be Jews without any apparent stigma attached to their identity. Their politics tended to be rooted in the unequivocal rejection both of the Soviet past and of any political movement deemed or imagined by them to be aligned with the abandoned empire.

Transplanted to U.S. soil and, for the first time in their lives, faced with political choices, many of them discovered that they were conservative. They became proud and loyal U.S. citizens and often voted for those who shared their passionate attachment to Israel and distaste for “socialism.” They hardly saw themselves as Russian or Ukrainian or Moldovan but rather as Russian-speaking Jews who emigrated from the Soviet Union. Which is not to say that they had no affinity for Russian culture and language — many of them did, and sometimes with vengeance.

There is no person in the United States who should be able to understand the nuances of Soviet Jewish identity and the trauma underlying the Jewish experience in the former Soviet Union better than Alan Dershowitz. For decades, he has been a figure of admiration among former Soviet Jews. A close friend of the legendary refusenik Natan Sharansky, Dershowitz was one of the most active and influential figures in the movement to free Soviet Jewry.

That is why it was so shocking and disappointing to see the prominent Harvard Law professor stay silent during the now infamous Fox News panel and Ingraham and Woo’s free-wheeling defamation of Vindman. I could not wrap my mind around the uncomfortable fact that someone who had done so much for so many Soviet Jews could sit calmly while the loyalty and integrity of one such Jewish immigrant was being questioned by those who are not worthy of approaching his record of service and excellence.

Thankfully, Dershowitz did eventually speak. In an Oct. 30 opinion piece for the NY Daily News, Dershowitz wrote that he remained silent because he “had never heard of Vindman and had no idea why he was being attacked,” adding that after he “looked up Vindman and found out that he was a great patriot, an American military hero and an immigrant from the Ukraine,” [he] immediately tweeted, “I don’t believe that Vindman is guilty of espionage or other crimes. … Vindman is a patriot who served his country. I’ve long opposed the criminalization of political differences.”

In his opinion piece, Dershowitz added that “the unfortunate attack on Vindman is a symptom of a deep malignancy which threatens our body politic.”

John Woo has since backpedaled as well, writing in USA Today that he has “no reason to question Vindman’s patriotism or loyalty to the United States,” but that he “thought the Ukrainian contacts sounded like an espionage operation by the Ukrainians.”

Those who subscribe to the clichés of the American success story would be hard-pressed not to admire Alexander Vindman’s American odyssey. Yet the moment Vindman resolved to uphold his oath and testify about the apparent malfeasance he observed within the Trump administration, the proverbial gloves came off and the friendly masks fell.

By all available accounts, Vindman is a profile in courage and civil service par excellence, a military man and self-effacing but efficient civil servant. He was also part of the third immigration wave that washed thousands of Soviet Jews onto American shores during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

As was typical of that cohort, he grew up an American patriot, which was not all that difficult considering that his family moved to the United States from Soviet Kyiv when Vindman was 3 years old. While most Soviet Jewish immigrants encouraged their children to follow predictable and safe career paths (medicine, engineering, computer science, law, etc.), the Vindman boys dedicated their professional lives to the military and civil service.

Even if it was not Ingrham’s intention, in the Fox News segment, this wounded war vet and a recipient of the Purple Heart ceased to be an American patriot and became, in the words of Zola (and the ears of today’s anti-Semites), a “dirty Jew.”

“It is a crime,” Zola wrote in J’Accuse, “to poison the minds of the meek and the humble, to stoke the passions of reactionism and intolerance, by appealing to that odious anti-Semitism…”

Are the attacks on Vindman just another case of the ends justifying the means? The joy of being close to power? The attractions of contrarianism?

As a historian, I believe in our ability to connect with the past. I can easily imagine Alan Dershowitz transported to Paris in 1906 and meeting Alfred Dreyfus soon after his exoneration. I see the two of them taking an unhurried walk together along the Seine. It seems to me they would have a lot to discuss.

Maxim Matusevich is a professor of history at Seton Hall University.

48.0°,

Light Rain

48.0°,

Light Rain