The Kosher Bookworm on Kristallnacht: Prelude to destruction

An historical account by Sir Martin Gilbert

Issue of Nov. 14, 2008 / 17 Cheshvan 5769

Last week marked the 70th anniversary of Kristallnacht. On the nights of Nov. 9 and 10, 1938, gangs of Nazi thugs roamed through Jewish neighborhoods across Germany and destroyed Jewish-owned shops and burned down synagogues. Over 1,000 synagogues were destroyed and almost 7,500 Jewish owned businesses were physically wiped out. In addition, over 25,000 Jews were sent to concentration camps.

This pogrom represented what is now regarded as the beginning of the end for the German Jewish community and the beginning of the program for the elimination of the Jews of Europe. These riots marked a major transition in Nazi policy and were the harbinger of what was to become the final solution — the Holocaust.

The surviving German Jewish community founded by Rabbi Joseph Breuer of Frankfurt has long preserved the Kristallnacht legacy here in America. Rabbi Breuer survived Kristallnacht only to be rounded up for incarceration in a concentration camp. He was miraculously released and subsequently escaped to New York, where he re-established his kehillah in Washington Heights.

Both he and his successor, Rabbi Shimon Schwab of blessed memory, wrote numerous essays on the Kristallnacht experience and of its theological as well as historical import in Jewish history. Each of their essays, found in their selected writings, deserve your reading. They give added meaning to an event that would otherwise be forgotten in the stream of other tragedies that were to occur in the years ahead.

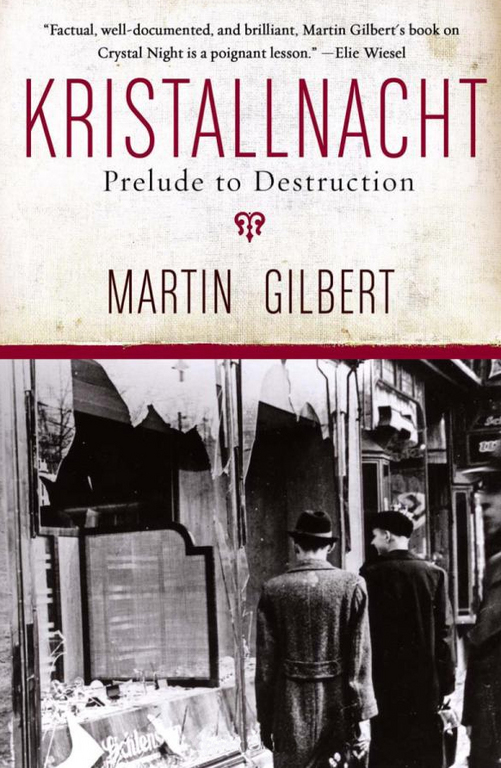

The definitive book on Kristallnacht is entitled “Kristallnacht: Prelude to Destruction,” by Sir Martin Gilbert, of the United Kingdom, one of the most distinguished historians of the World War Two era. Published in 2006 by Harper Collins, it recently has been reissued in paperback both here and in the UK.

Gilbert’s style is a conversational tone that immediately engages the reader’s attention. It draws even the most detached reader into the action being detailed. The reader is made to feel a part of the unfolding tragedy; not merely an observer. Gilbert’s method is how history is meant to be written and read, which explains the popularity of his writings. Numerous maps and statistics enhance an already effective narrative.

As a father and grandfather, I was most taken by the story of Esther Ascher, a 14-year-old girl whose “non-Jewish” appearance made it possible for her to observe with her own eyes the pogrom that destroyed her uncle’s store. She also witnessed the roundups of Jewish men destined for the concentrations camps, whose very existence was kept from the average German civilian, at that time.

Gilbert makes it clear from the outset that Kristallnacht was a turning point in world history; it hastened the onset of events that led to the war and the near destruction of a Jewish community that had lived on the European continent since Roman times, predating Christianity itself in Europe.

The depth of detail reflects research that is deeply appreciated by this writer, presented in a manner that gives the events it describes meaning as well as substance. Gilbert knows how to stimulate a reader’s interest, something that has been lacking in the writing of others; he makes history a vibrant and popular subject, especially for our youth.

Emblematic of the Kristallnacht experience was the destruction of almost every synagogue in Germany and Austria within the span of two days. This was a direct assault, not upon a political opponent, but upon a religion, its faith and beliefs, its sacred institutions and its adherents.

It is only appropriate that the commemorations held this year occured within the sanctuaries of synagogues, thus putting to a lie the attempt by the Nazis to wipe out an institution that has served as the center for Judaism for all its existence.

48.0°,

Light Drizzle Fog/Mist

48.0°,

Light Drizzle Fog/Mist