The art of coming back

Years ago, my mother clipped a newspaper column for me to read. At that point, I was more Israeli than American, and when I saw the long last name of the writer, “Krauthammer,” I associated it with intelligence and sharp writing. From then on, my mother would regularly clip Krauthammer columns for me. They would be stacked up on my dresser upon my visits home.

The brilliant columnist with the long last name would mold my way of thinking. Long before I ever dreamed of becoming a columnist, it was Krauthammer’s Pulitzer-quality writing that became my benchmark.

His colleagues’ summation of his work says it all: “Towering intellect.” “Piercing clarity.” “Voice of a generation.” “Agree or disagree, you had to consider what he wrote.” “Timeless wisdom.” He was the unequalled mind, the unequalled writer, an unequalled role model. I, along with millions of Americans, have been touched by his writings and by the life he lived.

As the years passed, when political developments arose, I often found myself thinking what would Krauthammer say? His column brought clarity and insight; he made me think. His words were my political North Star.

Krauthammer’s passion for politics was a motif in many of his columns. As he wrote in “Are We Alone In the Universe,” there could be no greater irony: “For all the sublimity of art, physics, music, mathematics and other manifestations of human genius, everything depends on the mundane, frustrating, often debased vocation known as politics. Because if we don’t get politics right, everything else risks extinction … fairly or not, politics is the driver of history.”

What resonated the most for me were his rare personal columns. While the implied wisdom of Socrates that “the unexamined life is not worth living” is a given, in “Beware The Study of Turtles,” Krauthammer balanced that view by warning of “the too-examined life.”

“Perhaps previous ages suffered from a lack of self-examination. Our problem is quite the opposite.”

“It is an overrated pursuit,” as is our obsessive “quest for self-love.”

He encouraged an organic, hard-working approach to self-love with a compressed phrase: “self-esteem follows achievement.” He counteracted paralyzing self-absorption with “Act and do and go and seek.”

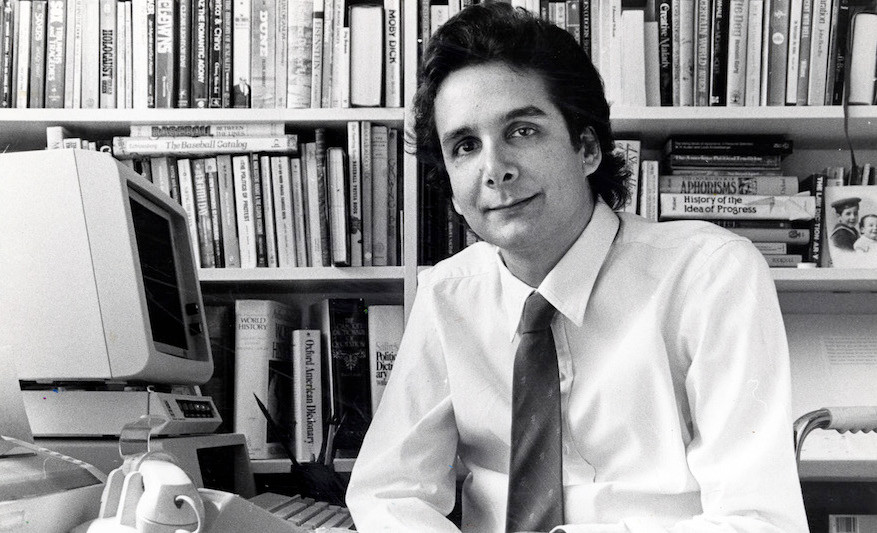

But Charles Krauthammer “was not only just one of the best columnists of our time,” as he described his friend and colleague Meg Greenfield. His thoughts were outgrowths of a unique life — a man of letters, with philosophy a degree from Oxford; a man of science, with an MD from Harvard. He was Jewishly educated. More than anything, though, Charles Krauthammer was indomitable.

He poignantly captures a universal spirit of growing up, painting a picture of his idyllic childhood — “the golden youth of our childhood” — shared with his only brother. “Ever brothers. Ever young. Ever summer,” ends the column in “Marcel, My Brother.” “My brother Marcel died on Tuesday, January 17. It was winter.”

Throughout the column, a love of sports shines through their boyhood: “For those three months of endless summer, Marcel and I were inseparable, vagabond brothers shuttling endlessly on our Schwinns from beach to beach, ballgame to ballgame. Day and night we played every sport ever invented . . . for a couple of summers we even wangled ourselves jobs teaching at the splendidly named Treasure Island day camp nearby.”

At the end of his first year of medical school, Krauthammer took a day off to enjoy the outdoors. In a freak diving accident, his fate was sealed. A strapping six-foot-one athletic young man was paralyzed from the waist down.

How did he go on?

“I don’t like when they make a big thing about it,” Krauthammer commented in a Washington Post interview in the 1980s. “The worst is when they tell me how courageous I am. There’s nothing ennobling about disease. And there’s nothing degrading about it. It’s a condition of life.” He did not want his accomplishments to be measured by a handicapped yardstick.

Writing afforded his ideas the opportunity to be evaluated on their own merit, his handicap invisible to the reader. The same went for television — the table, or screen, masked his wheelchair. People had no clue. Just as Krauthammer wanted it.

In Krauthammer’s last column, he wrote: “… the catastrophe that awaits everyone from a single false move, wrong turn, fatal encounter. Every life has such a moment. What distinguishes us is whether — and how — we ever come back.”

Not only did Krauthammer come back, his superhuman and dignified life of accomplishment, endurance and overcoming difficulty with grace modeled the essence of coming back. To witness to the life of Charles Krauthammer was to witness resilience in action.

His final column was titled, “A Note To Readers.” Without a trace of bitterness, he bid farewell in his characteristically humble manner:

“I am grateful to have played a small role in the conversations that have helped guide this extraordinary nation’s destiny … I leave this life with no regrets. It was a wonderful life, full and complete with the great loves and great endeavors that make it worth living. I am sad to leave, but I leave with the knowledge that I lived the life that I intended.”

I mourn a man who had great influence on my life.

Charles Krauthammer died on Thursday, June 21. It was the first day of summer.

Copyright Intermountain Jewish News

54.0°,

A Few Clouds

54.0°,

A Few Clouds