Teaching from home

Educating children in an unconventional way

By Yaffi SpodekIssue of Sept. 5, 2008

Most parents of young children share the common experience of the stressful morning rush to the school bus and the after-school challenge of getting everyone’s homework done. But Jessie Fischbein, a mother of three from Far Rockaway, has never driven a carpool or attended a parent teacher conference, and her children have never spent a day in the classroom. Outside their home, that is.

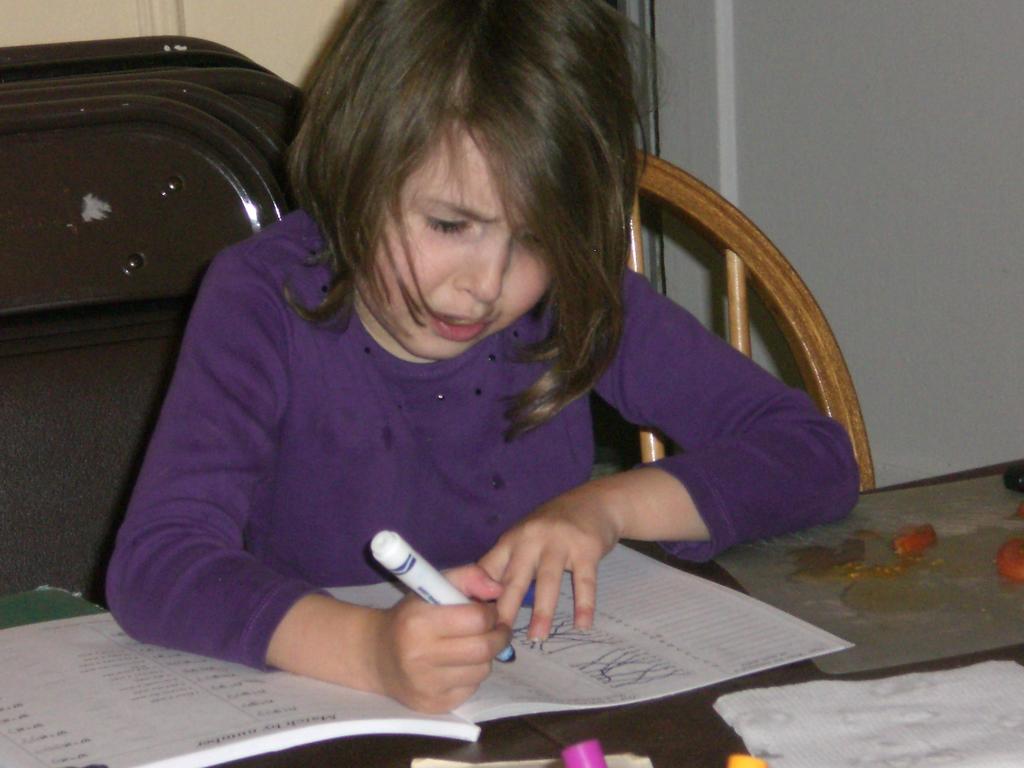

Fischbein homeschools her two older children, Sarah, who is technically entering eighth grade, and Chana, who is going into second grade.

“I was never planning to do it, I think I actually fell into it,” said Fischbein, describing how she became involved in homeschooling.

Fischbein was originally hired to teach a friend’s child who was “very inquisitive and curious,” she recalled. “It was just so much fun to follow his mind and how he learned and I thought it was a nice way of learning.”

From there, the group expanded to include her daughters and several others. At one point, there was a second teacher, a friend of Fischbein’s who was helping out. Eventually, the other children matriculated into the regular school system, but Fischbein decided to continue educating her children on her own.

“I started by teaching my own children how to read and every year we just keep going and building from there,” she said.

Other homeschoolers, such as Rochel Leah Itzkowitz of Elizabeth, NJ, originally sent the first six of her eight children to school and later decided to take them out for several reasons.

“I started homeschooling in 2003, because we had a lot of kids in school, the teachers weren’t always that great and the kids came home with tons of homework,” Itzkowitz explained. “On top of that, it was very expensive and we just didn’t feel that it was the only way to go.”

Prior experience working as an assistant teacher helped Itzkowitz decide that she was qualified for the task of homeschooling.

“If a veteran teacher trusted me to teach the kids in school, apparently I can handle it to some degree,” she said. “But, I wanted my kids to know that there had to be schedules and responsibilities, with books, tests and homework. We’re not ‘unschoolers.’”

The Itzkowitz’s living room has been cleaned out and converted into a classroom. The morning is dedicated to Hebrew subjects, loosely modeled on the curriculum of local yeshivas. Secular subjects are studied from an English curriculum provided by the Calvert school, including lessons, homework (incorporated into the lessons), reviews and tests, which are mailed away and marked by an outside authority. The students receive grades and transcripts that allow them to move up a grade each year, like a regular accredited private school.

For the older kids, the lessons amount to what can be compared to independent study, with Itzkowitz acting as a proctor to guide them and explain anything they can’t grasp on their own, while she spends more time teaching the younger children.

Fridays are more relaxed, and are often dedicated to home economics, arts and crafts projects and trips.

Fischbein has a more laid-back style of teaching. When she first began, she felt that her daughters needed an organized schedule, making sure to cover each subject for equal amounts of time. But now, “every year it gets less and less structured,” she observed. “As time went on, I realized there are just a few things I need to stay on top of...Everything falls into place with a little more time or extra tutoring.”

There is no homework and no tests. Fischbein explained that she teaches her daughters, one on one, at their own pace from a curriculum that she created, focusing more on subjects which interest them at different stages of their education.

“Some years we can work more on one subject than another subject and leave it for a different year when they would be more inclined or able to do it,” she said.

For Judaic studies, Fischbein teaches her own curriculum and the girls completed sefer Vayikra this summer. This year, she plans to cover Bamidbar and Devarim. For secular subjects, they follow a math curriculum from fourth to eighth grade and take books and readers out of the library for English. Science is taught almost completely through hands-on experiments, complemented by field trips to museums and workshops.

“I had my daughter read Rashi for a rabbi at one point, like a bechina to see where she was at, but the secular studies I don’t really worry about,” Fischbein elaborated. “They take a standardized test at the end of every year to show that they’ve completed a year’s worth of secular material.”

Though they are happy to homeschool, both Fischbein and Itzkowitz concede that it is a disadvantage for their children in terms of their social lives and ability to foster relationships.

“They have expressed interest in going to school, more for social reasons, and they sometimes miss that,” said Itzkowitz. She explained that since they did attend regular school for several years, they still maintain relationships with friends from there, and to stay connected, her son attends the hockey practices of the team at his former yeshiva.

“Most people ask about socialization,” said Fischbein. “It really hasn’t been a problem until more recently. As her [Sarah’s] friends began going to school, she has more of a dearth of friends now, and friends moved away so it’s harder for her.”

The Fischbeins also belong to a homeschooling network called LIGHT, Long Islanders Growing at Home Together, which organizes outings and workshops for homeschooled children and their parents to participate in and discuss their mutual experiences.

Though she does have friends, Sarah has expressed a desire to attend high school next year, and according to her mother, has said that she wants to “hang out with 10 girls every day all day.”

“But, if she doesn’t like it, she can always come back home,” said Fischbein.

56.0°,

A Few Clouds

56.0°,

A Few Clouds