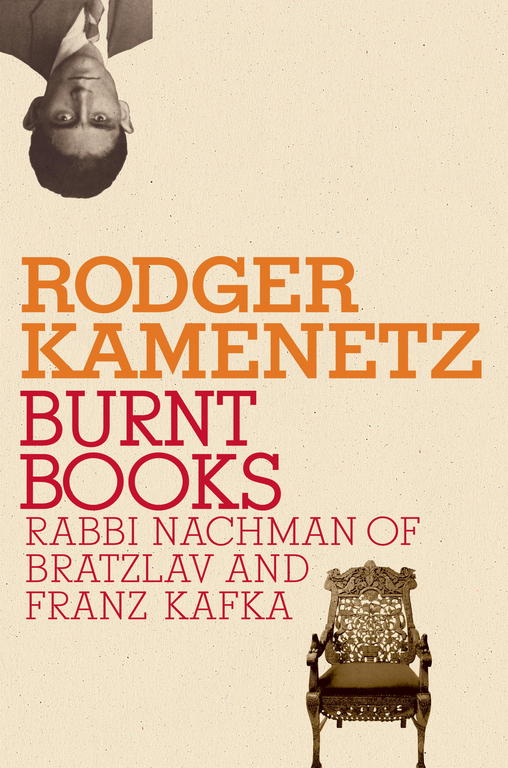

Q and A with Rodger Kamenetz: Kafka meets Rav Nachman

Michael Orbach: What are the similarities between Kafka and Rav Nachman?

Rodger Kamenetz: I think both of them are engaged in the same questions and that is reflected in their fictional writings. That’s where I begin. Gershom Scholem said that Kafka was the doorway to Kabbalah in our time.

There are a lot of similarities in their lives. Both men had cyclical personalities: ecstasy to extreme depression. Both men died close to age 40 from tuberculosis and both men asked their best friend to burn their writings. The opening part of the book engages in this question of burnt books. It’s a very vexing question about Kafka: what did he really mean by leaving notes to Max Brod that his writings should be burnt? Rav Nachman had written a book that he felt he had to burn and it’s now known as the “Burnt Book.” The exploration of these two questions and comparing these two thinkers is really the opening question of the book. The middle [of the book] explores striking similarities in their writings: tales about messengers; tales about an unjust legal system. There’s a story Kafka wrote, “The Judgment,” the day after Yom Kippur, about a father’s sentencing his son to death , and there’s a story by Rav Nachman called “The Rabbi’s Son,” where a father causes his son’s death.

The last part of the book is about journeys. Rav Nachman made an historic journey to the land of Israel and Kafka died dreaming of journeying to Israel.

MO: What biographical information do we have about Rav Nachman and what did he accomplish?

RK: We have a strong record of him and we see him through his chasid, Rabbi Nathan who is the source of most biographies. He was born in 1772 in Medzhybizh, the great-grandson of The Baal Shem Tov. Last Saturday was the 200th secular anniversary of his death. I would say he represents a generation of Chasidic leaders who were seeking to reinvigorate Chasidism to its core passionate truth after a time when it had become more established and more materialistic.

MO: How would you describe Kafka-esque? Is it being uncomfortable with the modern world?

RK: When I was researching on Google, I found 70 entries in one day. The most common was the sense of absurdity and malevolence of large bureaucratic systems. Young people who have to go through them relate to it. Kafka’s prominence is worldwide. A new book is published about Kafka every 10 days. Kafka goes far beyond the Jewish world and many critics see nothing Jewish in Kafka. My brief is to bring the Jewish Kafka back. That’s why I’m interested in Kafka being the doorway to Kabbalah. In terms of what’s common: they’re both drawing on the Chasidic parable. Kafka probably read the tales of Rav Nachman. Martin Buber [the Austrian Jewish philosopher who translated Rav Nachman] was using Chasidism as a way to invigorate secular assimilated Jews, Kafka was one of them. He represented assimilated Jews at the end of the Haskala when the streets were full of anti-Semites. The theory of being a Jew in the home and a man on the street was falling apart. He was part of the first generation to be more Jewish than their parents. Kafka studied Hebrew; he championed Yiddish actors; he dreamed of going to Israel and he was interested in the Chasidic parable; he said it was the only piece of Jewish literature where he always felt at home. That was important because Kafka was all literature, he once wrote he was “made of literature.”

Kafka’s parable “The Man from the Country” is about a man from the country who comes to the gate of the law, but the gatekeeper will not let him pass. Man from the country is an exact translation of “Am Ha’aretz.” Kafka’s stories represent the duality of being “Jewish at home” but” men on the street” . That is to outward appearances they appear like ordinary stories, but inwardly they are extremely Jewish. In the same way, Nachman expanded Chasidic parables by creating elaborate tales that are full of Kabbalistic references. He clothed Kabbalah in fairy tales. Both Kafka and Rav Nachman drew on the Chasidic parable and were very original in their recreation of it.

Kafka’s story, “The Metamorphosis,” was translated into Yiddish as “Der Gilgul.” In this most celebrated of his stories, Gregor Samsa wakes up as a bug. He’s a human being trapped in animal form, which is the concept of gilgul as punishment. Rabbi Nachman believed in gilgul. His little parable, ‘The Turkey Prince’ could be compared to “The Metamorphosis”. The difference is that in Kafka, there is no holy person to save Gregor Samsa. But in “The Turkey Prince” the wise man or rebbe does know how to heal the mad prince who thinks he’s a turkey. Both stories, in my view, are about the perils and risks of assimilation.

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy