Nuke race in Mideast casts long-term shadow

The danger of a Middle Eastern nuclear arms race in the near future is casting a shadow over the long-term future of a region that already has its fair share of security problems.

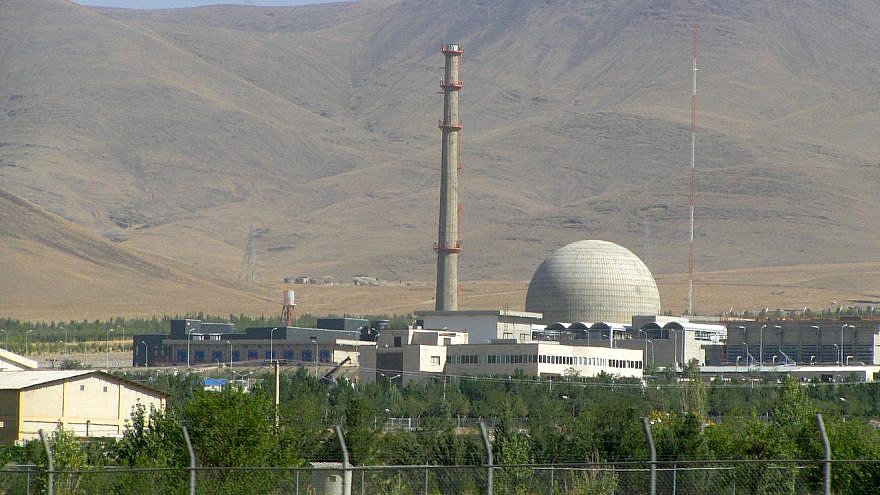

While such a race has yet to break out, former Israeli security officials have told JNS that several Sunni states in the region are watching Shi’ite Iran’s nuclear project with concern and could in future set up their own nuclear programs to counter the threat of a “Shi’ite bomb.”

Recent reports of an alleged new Saudi ballistic missile base have served as a reminder of a vow by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who warned in 2018 that if Iran acquired nuclear weapons, Saudi Arabia would follow suit.

For now, a number of Sunni states are creating civilian nuclear-energy programs. But such programs could in the future act as “shortcuts to military projects,” said Shaul Shay, a former deputy head of the National Security Council of Israel.

“Russia is the main supply source for the technology and the building of cores, as part of its economic and strategic interest,” he said.

A key to avoiding the outbreak of runaway nuclear proliferation in the Middle East is to stop Iran’s atomic ambitions, he argued.

“Israel must activate its influence to curb the Iranian nuclear project, in cooperation with the U.S. and Arab states,” Shay stated. “There also needs to be tight supervision of the civilian projects in Arab states.”

The international community, for its part, must plays its role in restraining Tehran’s nuclear program, he added, noting that “there are states like Saudi Arabia that declare that if Iran will have nuclear weapons, it, too, will obtain this capability.”

Ultimately, he said, Israel has a “limited ability to influence the situation, and most of the burden is on the U.S., which must lead the processes.”

In a report published by Shay in February 2018 for the Institute for Policy and Strategy at the Herzliya Interdisciplinary Center, he wrote that countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) “have legitimate reasons to develop nuclear energy programs, but the nuclear initiative among the MENA countries can be also viewed as a response to the Iranian nuclear program in the context of their strategic competition with Iran.”

Shay warned that “the Middle East is in the process of going nuclear … several countries including Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and UAE have announced plans to build nuclear power plants and over the next decade.”

“Iran’s program has already triggered a number of civilian nuclear programs in other Sunni Arab countries,” he stated.

Chuck Freilich, a former deputy Israeli national security adviser and author of Israeli National Security: A New Strategy for an Era of Change, told JNS that prospects of a multilateral nuclear Middle East do not form “an immediate threat.”

“The Iranians, who are more advanced and sophisticated, certainly in nuclear scientific studies, have been working on this for 30 years and still don’t have nuclear weapons. Israel has prevented it. The other candidates — the Saudis, Egyptians and Turks — are 10, 20, perhaps 30 years away from reaching a capability. Maybe only the Saudis can do it faster, if they buy turnkey technology from Pakistan. But it is not simple,” explained Freilich.

While not immediate, prospects of a nuclear arms race in the Middle East would be a “strategic nightmare” if they materialized, he cautioned. “These are not the capabilities that the Soviets and the U.S. had; it would not be the end of humanity. But the chances that someone might use these weapons in the Middle East are much higher,” Freilich argued.

The kind of deterrence and de-escalation paths that were available to Washington and Moscow during the Cold War, or “even to India and Pakistan,” are not present in the Middle East, warned Freilich.

“Here, at least one state is calling for the destruction of others. The Americans, Soviets, Indians or Pakistanis never had that objective,” he noted. “The Americans wanted to end communism; the Soviets wanted to topple capitalist democracy. No one wanted to destroy the other.”

The Shi’ite theocratic regime in Tehran is “a very rational player, [but] its rationality is different from others. Its willingness to take risks is higher.”

Freilich said “the Saudis disconnected diplomatic relations with the Iranians. The Egyptians and the Iranians have not had links for decades. How do you manage a nuclear crisis without communications, and when you have seconds or minutes to act?”

And he echoed Shaul’s call that the key to avoiding a nuclear arms race rests, first and foremost, with stopping Iran from going nuclear.

At the same time, if Iran did end up going nuclear, there would be “no real solution” to a Middle East with multiple nuclear states, Freilich said. Israel ending its nuclear ambiguity would not have a major effect, he assessed, since all regional actors already assume that Israel is a nuclear state.

Freilich said he wouldn’t be surprised if the Syrians are trying to renew their nuclear program under the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad. Israel destroyed the nuclear-weapons production site in eastern Syria in a 2007 airstrike.

In his report, Shaul noted that in 2017, Egypt and Russia’s Rosatom energy cooperation signed a document to launch an Egyptian nuclear power plant west of Alexandria.

Saudi Arabia announced in 2011 that it planned to build 16 nuclear-power reactors by 2030 at a cost of $100 billion, which would generate around 20 percent of the country’s electricity needs.

Jordan, which currently imports more than 95 percent of its energy needs, plans to create nuclear power to generate 30 percent of its electricity needs by 2030. South Korean constructors built the Kingdom’s first nuclear reactor in 2013.

The UAE has built the first nuclear power plant in the Arab world. A further three South Korean-designed reactors are under construction.

49.0°,

Fair

49.0°,

Fair