Jerusalem tales: Seven gates to the city

Originally published July 16, 2010

Every week now for the past half year there seems to be no letup in the growing quarrels between the diverse groups within the Orthodox Jewish spectrum and non-Orthodox Jews.

These seemingly petty disputes, over time, have evolved from rhetorical battles to physical ones, and have served to sully our image and create a public desecration of our faith.

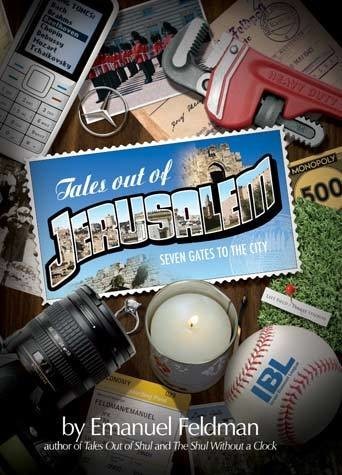

In the books I was reading prior to my trip to Jerusalem this month I came across a volume by one of our faith’s leading interpreters, Rabbi Dr. Emanuel Feldman. Titled “Tales Out Of Jerusalem” (Feldheim, 2010), this book contains a series of short essays, organized into seven sections, dealing with the gamut of issues facing us today. Rabbi Feldman seeks to give the reader a rational and responsible opinion on issues others fear to tackle, and he does so with both charm, wit, and firmness in tone.

While tied to Jerusalem, the book deals with issues that transcend both the geographic and as spiritual confines of the holy city. One example is an essay originally composed in 2005 and deemed contemporary enough for the good rabbi to include in this volume. It is to this essay that I wish to center my review for its content both speaks to the issues of today and represents all the eloquence to be found in this brilliant anthology.

“Ready to be Orthodox but no place to go” reads like a heartfelt plea for sanity in the ongoing disputes between the Modern Orthodox community and the Charedi community.

Rabbi Feldman gives candid observations of both the faults and strength’s that are to be found within these diverse groups. Each group is given their due as to the sincerity of their motive and purpose. The group’s devotion to faith is not questioned, rather he questions their actions and the sincerity of those actions.

Rabbi Feldman’s frankness is refreshing. Consider the following observation: “I fully appreciate the sacrifice that full-time kollel learning involves: many luxuries and comforts are happily surrendered in order to maintain such dedication. But within their world, is there also room for genuinely pious and learning people who also work, earn livelihoods, and have university degrees?”

However, Rabbi Feldman also gives the following as a retort to those who seek to bash the kollel mindset:

“They [the chareidim] have a charismatic leadership, a consistent ideology, they are intensely Jewish, they sacrifice,” Rabbi Feldman writes. “There is a purpose in their lives, spiritual strength, sanctity, self-assurance — and these have attracted many Jews under their umbrella.”

These observations, while not the final answer to the communal disputes that have bedeviled us of late, help frame a dispassionate discourse for the establishment of peace and tranquility as well as mutual respect among the diverse groups within our faith.

Absent from Rabbi Feldman’s observations and words of advice are personal attacks, demeaning characterizations and divisive images that further help to inflame an already incendiary situation.

It behooves us at this time of year to take Rabbi Feldman’s wise words to heart and to learn from them that there is balance to communal diversity, that disagreement in terms of theology and intensity of practice should not invite heresy hunting.

Sinat Yisrael should have no place in public parlance and that the Ahavat Yisrael learned from the pages of Rabbi Emanuel Feldman should be reflected wherever Jews live.

47.0°,

Fair

47.0°,

Fair