Civil War spy games

Posted

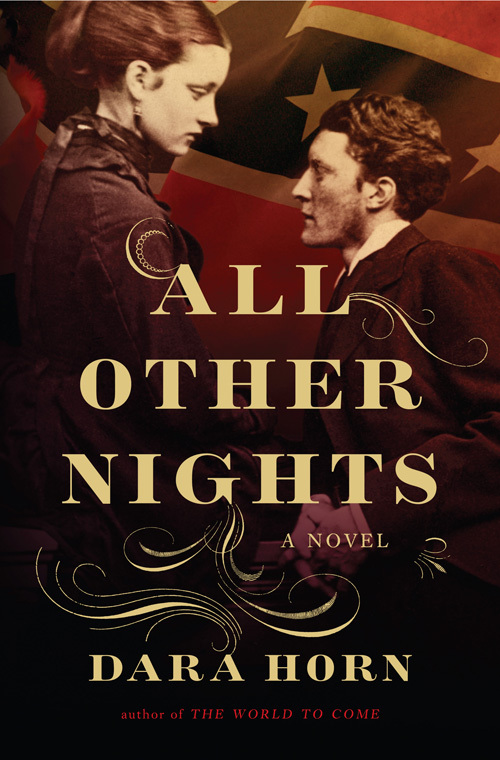

A review of All Other Nights by Dara Horn

Reviewed by Miriam Bradman Abrahams

Issue of November 6, 2009/ 19 Cheshvan 5770

Dara Horn is often asked what makes a book Jewish. It used to mean it was written in Yiddish or Hebrew, she replies. In the U.S. we have one of the largest Jewish communities in history, but we don’t necessarily communicate in a Jewish language. Horn interjects into her writing many ideas and phrases from the prayers and Tanach. She writes about morality, religious and biblical themes. Her latest, All Other Nights, “is not realistic,” she said. Rather, “it is a potboiler about the Civil War, written like a dime store novel with outrageous plot twists similar to some stories in the Torah.”

Jacob Rappaport is a Jewish soldier in the Union army who is ordered to New Orleans to murder his own uncle, who is plotting to assassinate President Lincoln. He is then assigned to marry an enemy spy, the daughter of a Virginia family friend. The book is based on historical facts including the story of Judah Benjamin and the African-American spy network. It is about loyalty, betrayal and repentance; the values of family and tradition and the pursuit of social and racial justice.

Horn compares Jacob Rappaport to the biblical Jacob in Sefer Bereishit. The biblical Jacob tricked his father, stole his brother’s birthright and is deceived by Laban when he wants to marry Rachel. He is a character in transformation that can be seen as a different man when he later mourns the death of his son Joseph. Jacob in All Other Nights changes from being a slave to others and living as a double agent to learning about the gift of free will and trying to act accordingly.

One inspiration for the book came from the author wandering around the Jewish cemetery in New Orleans when she spoke at a JCC there. After New York City, New Orleans had the second largest Jewish population during the Civil War. Many religious denominations split during the war, but the Jewish community did not. Unlike their gentile neighbors who were land-based, Horn explains that the Jewish community was mobile due to their businesses. Jews traveled north and south and knew people on both sides of the battle. Northern Jews brought matzah down for Southern Jews; both sides were known to host guests from the “other side” for Shabbat and holidays. Southerner David Einhorn was an abolitionist, while Rabbi Dr. Morris Raphall, head of New York City’s Congregation Bnai Jeshurun was pro-slavery. He was the first rabbi invited to the White House.

I’ve had the pleasure of meeting the author a few times and am impressed by how comfortably she presents her work to an audience. She is young, brilliant, personable and funny too, sharing anecdotes about her family life. Winner of multiple awards, she relays her thoroughly researched facts into clearly elucidated themes while keeping the reader engrossed in the exciting plot. Horn received her Ph.D. in comparative literature from Harvard University studying Hebrew and Yiddish. She is one of Granta magazine’s Best Young American Novelists, and has received a National Jewish Book Award for In the Image and The World to Come. She earned Hadassah’s prestigious Ribalow Prize for The World to Come. That book and All Other Nights were New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice. She has taught Jewish literature and Israeli history at Harvard and Sarah Lawrence and has lectured throughout the U.S. and Canada.

During a presentation at Hadassah’s Nassau Region, Horn passed around a $2 bill from the Civil War featuring Judah Benjamin’s picture. Judah Benjamin “lived nine lives.” He was the Confederacy’s Secretary of State and spymaster, Jefferson Davis’ closest confidante and second-in-command. He was born in the Caribbean to Sephardic parents and was the second Jewish senator. When the confederacy collapsed he escaped to England and became Queen’s Counsel. He was hated by both the north and south and was known to smile when he was insulted.

Jews have found themselves cast in the role of double agents for a long time, Horn noted, offering the Conversos of Spain as an example. Jews could never fully be themselves in public and in her story, the only time they felt free was during Sunday morning church services. That’s when they could relax their guard and take to the streets. Jews in the South benefited from racism because they were considered white, while in the more homogeneous North, Jews were considered “ethnic.” She feels that Jews have always had the “burden of proof” but that the founding of the State of Israel has removed that issue.

Historical novels are more about the time in which they are written rather than about the period they cover, Horn feels. She explains that today we have political polarizations which may have their roots in the Civil War era. We have red states and blue states, and a divide between personal independence at all costs versus justice and equality at all costs. We have tension between tradition and progress, who we were born as and who we want to become. Many of our ancestors proved their loyalty to the U.S. by betraying their Jewish heritage. In America the idea of the “self-made man” is highly valued, while in Judaism we are a product of our heritage.

It has taken Dara Horn about two and a half years from the idea to the completion of each of her novels. She is also busy with an academic career and as the mother of three young children. When spending time with her husband, he shares about the people at work while she tells him about her imaginary characters. Dara is working on a new book but wouldn’t disclose the topic since All Other Nights began as another story which she scrapped. It seems that All Other Nights was going to be about the friendship between Mark Twain and Sholom Aleichem — “the Jewish Mark Twain.” She had the idea that they both knew Jacob Rappaport but ended up discarding her first 100 pages, she said, to write the story as it was finally published.

Well, I’m glad she did, but I’m sure her readers would have enjoyed reading about Mark Twain and Sholom Aleichem just as much.

Report an inappropriate comment

Comments

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast