Chabon’s abhorrent view increasingly mainstream

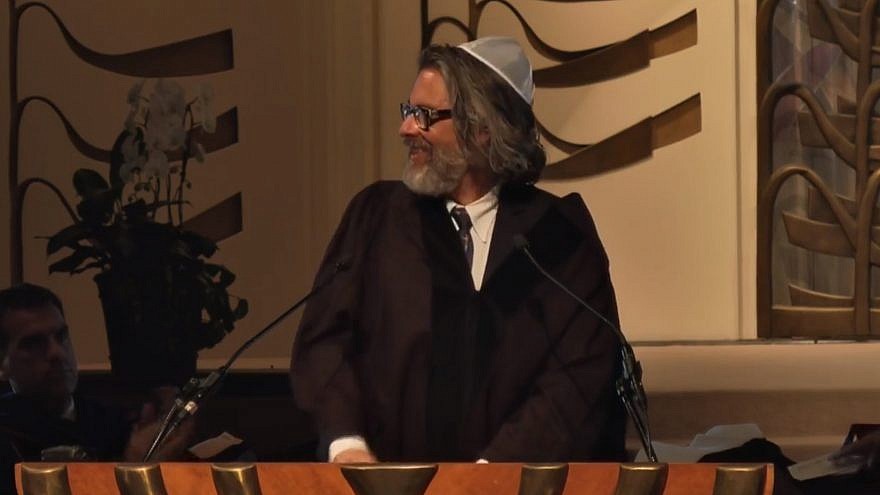

Michael Chabon gave the most remarkable commencement speech in the history of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Reform movement’s flagship seminary, inveighing against inmarriage as a sacred Jewish norm.

His words bear repeating, much as it pains us to write them: “An endogamous marriage is a ghetto of two. … It draws a circle around the married couple, inscribes them — and any eventual children who come along — within a figurative wall of tradition, custom, shared history, and a common inheritance of chromosomes and culture.”

Chabon urged the graduates and their parents to abandon advocacy for Jewish-Jewish marriage, rejecting the view that Jewish homes with a single identity are critical to raising Jewishly committed and competent children. Later, he underscored the seriousness of words by, in effect, doing teshuvah for having inmarried, and for having taught his four children that marrying Jews is preferred.

Chabon targeted the heart of Judaism itself, condemning the concept of havdalah (the Judaic value of distinguishing between entities), which he depicted as a “giant interlocking system of distinctions and divisions.” He specifically targeted Shabbat candle-lighting, monthly immersions in the ritual bath, circumcision, bar mitzvah and the Four Questions recited during the Passover Seder.

Even the Passover removal of leavened bread troubled this would-be slayer of Judaism’s age-old ethos.

Chabon extolled the virtues of outmarriage, declaring himself a devotee of “mongrels, syncretism, integrated neighborhoods, open borders, pastiche and collage,” and, above all, “miscegenation as the source of all greatness.”

It is important to recognize that Chabon’s call to abandon inmarriage is a symbol of a larger, more grandiose objective. Promoting intermarriage was the opening shot in a drive to dismantle Judaism and put an end to the inevitable injustices he insists religion perpetuates.

Not only is Judaism responsible for religious prejudice around the world, it is also responsible for its own demise: If Judaism disappears, Chabon asserted, “the fault for that extinction will lie squarely with Judaism itself.”

Chabon seemed content, even disturbingly relaxed, imagining the end of Judaism.

“If Judaism should ever pass from the world,” he said, “it won’t be the first time in history … that a great and ancient religion lost its hold on the moral imaginations of is adherents.”

What are we to say?

It is tempting to dismiss Chabon’s thinking as hyperbolic or unworthy of reply, perhaps performance art of a personal psychodrama in public. But Chabon’s undeniable, sometimes dazzling, talent as a novelist, and the high status he enjoys among elite readers, make it critical to respond.

Even more important, his perspective has been echoed in other corners of the Jewish community. Chabon’s ideas have cache, especially in culturally and political progressive bubbles, such as elite universities where Jews live in safe enclaves, experiencing privileged lives.

In fact, Chabon’s willful denial of intermarriage as a threat to the health of American Jewish life is common in many Jewish circles, outside of Orthodoxy, religious Conservative Jews, political conservatives and Jewish immigrant communities. Only one-fifth of Jews raised in Reform families marry other Jews.

Citing the fact that intermarried couples are proud to identify as Jews, the majority of American liberal Jews ignore the mountain of evidence that only a small minority of their adult children remain firmly connected to Judaism, Jewish community or culture. Only 8 percent of their grandchildren are being raised Jewish. Among the 7 million American adults raised by a Jewish parent, over 2 million deny they are Jewish. Few intermarried households are nearly as educated, connected or committed as their inmarried contemporaries.

Chabon’s views are worrisome because among liberal American Jews they are not outlandish. We live in an age that not only is opposed to behavioral norms imposed from above, but to social boundaries to our left and right. Jews, a tiny minority in a sea of over 300 million Americans, are being increasingly engulfed by the majority society — one blessed by a culture of tolerance, at least until recently.

Ideologically, our concept of peoplehood requires both respect for the outside culture and the transmission of our own. Distinguishing between Jews and non-Jews has made Jewish societies more tolerant, since according to Judaism only Jews must comply with Judaic law.

Once, some argued that intermarriage was inevitable and trying to prevent it was as futile as trying to change the weather. Chabon and those who share his values go a step further: they like the new weather. They view intermarriage as a positive development, not a step toward self-destruction.

Chabon’s assault on Jewish difference is dangerous, morally abhorrent and factually incorrect on at least four counts.

First, Judaism as a religious culture offers more than critical thinking skills. To take just one example: ancient Judaism, unique among world cultures, introduced an inclusive day of rest and mandated it for all socioeconomic classes, without exception. The Sabbath was a bold blow to what Chabon calls “the economics of exclusion.” Recognizing its virtue, Christianity and Islam adopted the concept from Judaism.

Millions of Jews cherish the cultural richness that the Jewish calendar brings to their lives — as Chabon and his family did, until recently. Millions are captivated by the intellectual wealth, wisdom and complexity of Judaic texts. For others, the warmth of community life is the compelling factor. Still others demand social justice in the name of Judaism, putting the directives of the prophets into practice in local and international settings.

Not least, for many American Jews, the opportunity to engage with Israel, the only country in the world whose language, culture and ethos are Jewish, is a source of joy.

Second, Chabon treated religious extremism as a Jewish monopoly. But worldwide — including the United States — large swathes of society have reacted to transnational change by retreating into sectarian enclaves. Yet Chabon declared that he would be fine with his children marrying into other religions that are as likely to produce intolerance and extremism as the Jews who provoke his fear and disgust.

Third, distinctiveness is not the enemy of creativity. Chabon’s rejection of distinction is revealed as a lie in his own justly acclaimed novels. His gorgeous, edgy, evocative language is the product of an author making artistic “distinction and divisions,” moving sentences from one paragraph to another. As Chabon well knows, only when artists define their own “boundaries and bright lines” can they create credible settings, provide each character with distinctive dialogue, and give each character life and dimension on the page.

Indeed, much of Chabon’s commencement address was curiously binary and judgmental — and bogus. We can all, like Chabon, love “pastiche and collage,” but distinctions are necessary to life and health, judgment and morality — to say nothing about science, families, communities and nations.

Finally, religious “syncretism,” which Chabon embraced, erodes ethnoreligious viability. Sociologists and historians provide powerful evidence of rich minority cultures that fade not because of their moral “fault,” as Chabon asserts, but because they could not maintain their distinctiveness. Minority cultures may not need to be sealed off, but to survive they all depend on living expression in the form of ethnic languages, music, arts, foods, texts, history, religion and folkways.

Marriages between two Jews, whether born Jews or Jews by choice, along with Jewish societies that support them, are demonstrably the most effective factors in Jewish vitality. They do indeed create a “figurative wall of tradition, custom, shared history and a common inheritance” — and, contrary to Chabon, that is a good thing. To deny this reality is to deny sociologically verifiable facts. Chabon may no longer care — but we still do.

Chabon naively envisions a utopian world where through wholesale intermarriage of all races, nationalities and creeds, all of humanity will be homogenized into a single “mongrelized” blandness. In practice, since Jews are a minuscule minority, this prescription would yield the disappearance of Diaspora Jews and Judaism. Christian denominations would be untouched. Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam would be unperturbed. The world would hardly notice — but it would be a world without Jews.

Jews with any historical sense have seen this before. Since the Enlightenment, Jewish cultural elites have proposed that the solution to the world’s ills is Jewish assimilation. If only the Jews would let go of their distinctive religious culture, the world would be redeemed.

Over past decades, the Jewish community has been marked by impassioned discourse over intermarriage. Though far from uniform, a “left” camp has argued for greater acceptance of intermarried families. The “right” has argued for holding on to distinctions — liturgical and otherwise — between the inmarried and the intermarried. Each camp sees the other as suspect, albeit in different ways. Those on the left don’t believe the right is sincerely committed to tolerance. To those on the right, the left’s promotion of “welcoming” has seemed like a stalking horse for total indifference, if not celebration, of intermarriage.

We urge proponents of inclusion — many of whom we count as dear friends and colleagues — to think about where they stand in regard to Chabon’s challenge. Where would you draw boundaries? Where do you stand on maintaining some distinctions between Jews and others? Is Jewish group survival a force for good or for ill, not only for individual Jews but for humanity? Should we teach the next generation that all Jews — both those born Jewish and converts — are in a kinship relationship with one another, as heirs of a unique, rich and valuable cultural heritage?

As Pete Seeger once asked, “Which side are you on? Which side are you on?”

Sylvia Barack Fishman is Joseph and Esther Foster Professor of Contemporary Jewish Life in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Department at Brandeis. Steven M. Cohen is Research Professor of Jewish Social Policy at HUC-JIR. Jack Wertheimer is Joseph and Martha Mendelson Professor of American Jewish History at the JTS.

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast