850,000 refugee Jews who fled Arab lands

November 30 is a day to commemorate approximately 850,000 Jews who fled anti-Jewish persecution across the Arab world in the 20th century. Every year on this day, I reflect on my own family’s story of exodus, and every year I find it gives me new insights into the story of Israel and the Jewish people.

This month, I spoke with a member of the Jewish “anti-occupation” camp. In the course of our discussion, he said that he prefers not to base his understanding of the world in fear.

The quip took me by surprise, but it seemed to provide the basis for many of his political positions. For context, we were discussing the Israeli security fence — each of us looking for the inconsistencies in the other’s argument.

He attempted to connect my support for Israel’s barrier with Donald Trump’s plan for a wall along the US-Mexico border. I protested, citing the reduction in the number of attacks from the West Bank since the barrier was constructed. He yielded, saying, “I can’t argue with that.” I was satisfied that I had bested my opponent with an argument grounded in fact. Then he said it. “I just prefer not to base my understanding of the world in fear.”

While the conversation focused on border security, I sensed that he meant to suggest that Israel’s creation was a product of fear.

Having reached an impasse, the conversation ended, but the sentence lingered in my ears and began to replace my self-satisfaction with self-doubt. I began to wrestle with a question: Is my support for Israel borne out of fear?

I looked to my grandparents — refugees whose stories have always been an inspiration for my exploration of Israel and Judaism.

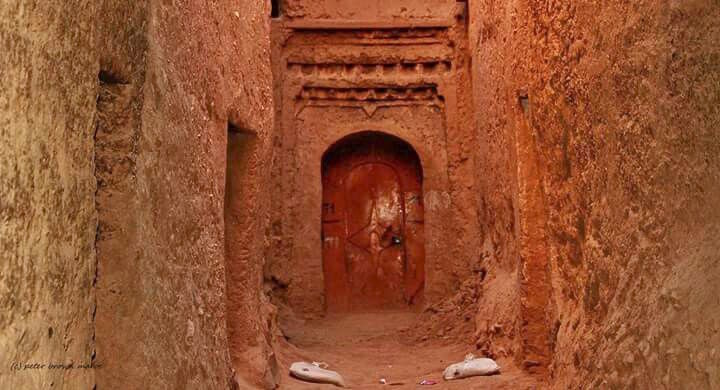

My grandparents, Savta Chana and Sabba Moshe, were born in Tinghir, Morocco, some time in the early 1930s. No one is quite sure of the dates because there are no records, so we celebrate their birthdays on Dec. 31, since they must have occurred at some point in the last year. Tinghir is a small village at the base of the High Atlas Mountains comprised largely of Amazigh people, also known as Berber.

In the early 20th century, Morocco was seen as a relatively safe place to be Jewish, thanks in large part to King Mohammad V, who famously responded to the Vichy government’s demand to list all of the countries Jews by saying, “We have no Jews in Morocco, only Moroccan citizens.”

However, Jews lived as second-class citizens, or dhimmi, in Morocco, subject to restrictions on their daily lives. In the two decades that followed the creation of the State of Israel, Morocco, along with the rest of the Arab world, was virtually emptied of its Jewish citizens.

My family suffered the consequences of being Jewish in the Arab world before and after the creation of Israel. I heard stories of riots targeting the Jewish mellah, a walled Jewish quarter akin to a European ghetto. The men of the family would, after hiding their wives and children, stand outside and fight for their lives. In one such instance, my great-grandfather was lynched by an angry mob, leaving my grandfather, a boy of 4 or 5 years old, without a father.

But based on conversations I’ve had with my family, I am certain it was not fear that drove their flight from Morocco, but a love for the Land of Israel.

To be sure, thousands of the Middle East’s Jewish refugees were forced to leave their homes behind — motivated by threats to their personal safety — but in searching for a new home, most chose Israel because of this love and devotion.

In our time, there is great reason for Jews to be fearful. A mass shooting at a synagogue in Pittsburgh, a neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville and a Labour Party leader in the United Kingdom whose words have left 40 percent of the country’s Jews considering emigration.

Even in Israel, citizens endure threats from hostile Iranian tyrants with armed proxies in Lebanon and the Gaza Strip. Israel is a young country whose citizens have endured loss since its creation. The scars of war and intifada, kidnappings, stabbings and car-rammings are etched deep in every Israeli’s psyche. The further back in our history you look, the more you realize that this has been the price Jews pay for their membership in this ethno-religious group.

I often wonder what possessed my family to remain Jewish through the years. In hostile lands, facing threats to their lives and more commonly the burden of their faith, it would have been easier to turn their eyes away from Zion. It is because they did not succumb to this fear that I can answer confidently that Israel is not a trepidatious project of self-ghettoization, as the person with whom I spoke may have suggested.

It is an expression of an enduring love that has survived millennia, built by Jewish refugees from across the world.

48.0°,

Light Rain

48.0°,

Light Rain